Lee Evans: Educating the World

Photo: David Schmitz

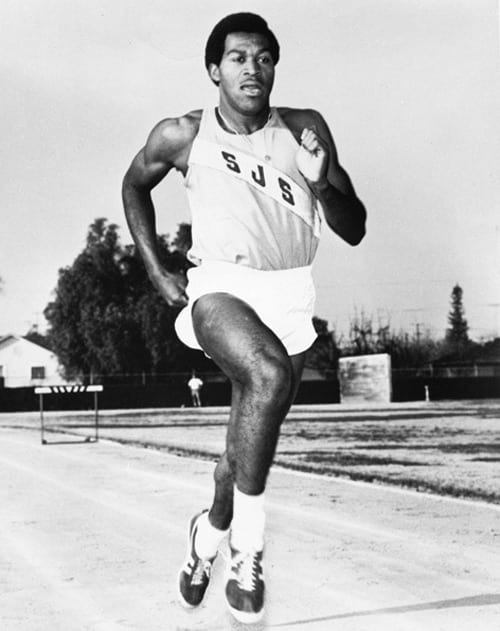

Olympic medalist and Olympic Project for Human Rights advocate Lee Evans grew up working in the fields of California’s Central Valley. His parents had migrated west from the Jim Crow South. Sport offered a new path—entry to higher education and a career in athletics.

“My mother used to take us out to the fields to help pick whatever was ready to be harvested,” says Evans, ’70 Physical Education, in a 2004 interview. “I grew up picking cotton and cutting grapes, and we did that from sunup to sundown. That’s how I always thought I got my special endurance.”

Evans first began running the 400-meter race at Overfelt High School in San Jose. By his senior year, his success with the 660-yard dash garnered enough attention to attract several offers of college scholarships. He became a Spartan to train with San Jose State’s legendary coach Bud Winter, whose methods and approach inspired him to travel the world, spreading the Speed City track and field gospel.

Credit: SJSU Athletics.

In 1968, Evans became the NCAA champion in 400 meters, which qualified him to compete internationally. When he wasn’t testing personal records, Evans was active in the Olympic Project for Human Rights at San Jose State. United by Harry Edwards, ’64 Sociology, ’16 Honorary Doctorate, and Ken Noel, ’66 BA, ’68 MA, Sociology, OPHR members threatened to boycott the Mexico City Olympic Games if the International Olympic Committee failed to meet their demands. Evans understood that the public discussion of a boycott was enough to attract media attention and saw competition as an opportunity to educate the world about racial, social and economic inequality. (Zirin 2004)

“A lot of students were having trouble finding apartments, and so Harry Edwards and Ken Noel started to organize us and help end segregation,” Evans remembered while on campus in 2016. “When you went to the starting line, you knew you had to represent because Harry Edwards is here, Ken Noel is here. Everybody who is involved in the Olympic Project for Human Rights is here, so you had to definitely win the race.”

At the 1968 Olympic Games, Evans earned gold in the 400 meter and the 4×400 meter relay, breaking records with each race. Once on the medal stand, he donned a black beret as a nod to the Black Panther Party, whose demonstrations in Oakland hit very close to home. While in Mexico City, Evans recalls receiving death threats from the National Rifle Association and the Ku Klux Klan. (Zirin 2004)

Following the Olympics, Evan completed his degree at San Jose State and ran professionally before moving abroad to coach Bud Winter’s sprinting techniques in Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, Cameroon and Qatar. He also coached with the U.S. Special Olympics. Motivated to help runners in the way that Winter had coached him, he spent more than 20 years on the continent, even purchasing land in Liberia with plans to establish a school.

“I used Bud Winter’s program because it was so successful with us,” he said at SJSU in 2016. “It was San Jose State’s program. I put it all over Africa and the Middle East.”

Throughout the years, Evans has been recognized for his contributions to sport. A Fulbright scholar in sociology, he received the Nelson Mandela Award for humanitarianism in 1983. He was inducted into the Olympic Hall of Fame in 1989 and the U.S.A. Track and Field Hall of Fame in 1993, and received the NCAA Silver Anniversary award for his work in Africa and Asia in 1994. An active educator and coach, Evans is still committed to passing on the traditions of San Jose State track and field to athletes around the world.

Reflecting on his moment on the international stage, Evans remembers praying before the race began—not to win, but to run to the best of his ability and to avoid injury. He says that his brother watched the race on television with their mother, who upon watching her son win gold, setting a world record that would hold for more than two decades, said, “He came from me.”

This is great! I love the Bud Winter reference because we can see that his life continues through the athletes!