Ken Noel: Reframing Possibility

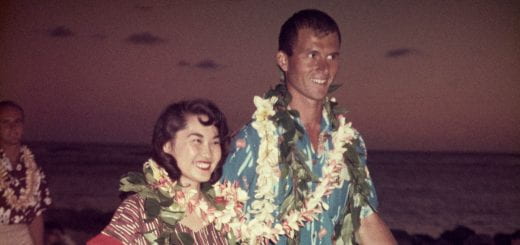

After the Olympics concluded, the OPHR turned its attention to other civil rights causes. Ken Noel taught sociology courses at San Jose State for 10 years and earned a PhD before transitioning to Silicon Valley tech, where he later retired. In 1970, he married Mary East, and together they raised children while staying active as educators, community activists and longtime civil rights advocates. As supporters of San Jose State’s Institute for the Study of Sport, Society and Social Change they are glad to see scholars investigating race, class, sociology and sport—continuing the conversation they started a half-century ago. Photo: David Schmitz

Photo: David Schmitz

When Ken Noel transitioned from an all-black elementary school to a predominantly white junior high school outside of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, he felt lost and alone. For the first time, he recognized that the options presented to him as a young black man were different—that he would be underestimated. Luckily, Noel had a knack for defying expectations and reframing possibility.

“I never got any encouragement in school,” says Noel, ’66 BA, ’68 MA, Sociology. “The only thing I ever felt strongly about was running because that was the most positive experience I had in the Jim Crow North. In junior high, I moved away from being academic and focused on running for a more positive self-identity. I became the 100m champion, the 200m champion, the 400m champion and the cross country champion.”

After graduating high school, Noel joined the Air Force and was stationed in Pensacola, Florida, where he met a young woman named Mary East. When a high school friend encouraged him to train at the Santa Clara Youth Village Track team, Noel hitchhiked cross country in 1960. His dual specialties as a sprinter and a distance runner made him a natural fit for the team, which was coached by the former Hungarian national team coach Mihály Iglói. He enrolled at San Jose City College before transferring to Texas Southern University in 1964, where he tied for first place in the NCAA College Division 880 yard run. He transferred to San Jose State in 1965, where he completed his studies.

While Noel fine-tuned his athletic ability on the track in community college, he encountered more of the “western Jim Crow” of 1960s San Jose. Housing discrimination was rampant throughout the Bay Area, so to find a place to live Noel had to hide in the back of his car while his white friend rented an apartment to share. For weeks he had to act like he was “just visiting” until the landlord grew used to seeing him around. That feeling of passing through—of not being allowed to settle down, enjoy the same rights and privileges as his white neighbors, classmates and friends—was engrained so deeply that Noel says for his first seven years in San Jose his primary goal was to “survive.”

“In the years leading up to 1967, we had concerns and we raised issues, but mostly we tried to survive as individuals,” he remembers. “We didn’t do anything as a collective until Harry Edwards and I sat down in the middle of campus one day and decided it’s time—we need change. We couldn’t have young kids coming in as freshmen facing the same difficulties we had faced. We organized a rally and kicked off a movement on campus that was consistent with the civil rights movement.”

Spartan Daily clip from January 1968.

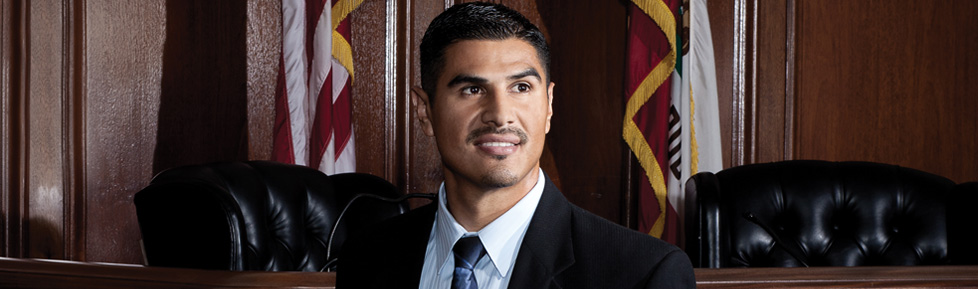

The United Black Students for Action was born. Noel was a sociology graduate student and Edwards, ’64 Sociology, ’16 Honorary Doctorate, was a lecturer. Edwards and Noel organized rallies, protests and events to bring together African-American student-athletes and fellow campus activists. Whether they were demanding that the university administration diversify its coaching staff, desegregate housing or communicate a non-discrimination policy, the UBSA cultivated a culture of activism—with an emphasis on action.

“The most positive thing about that time was that President Robert Clark basically agreed with our view,” Noel says. “He accepted the notion that black students were being channeled into certain majors. The athletics department wouldn’t recognize that there was stacking in football—which meant that they’d bring in three black football players and make them vie for the same position. They didn’t recognize that the distribution of employment for athletes was stratified—white students got certain jobs, black athletes got other kinds of jobs. Less pay, more labor intensive. They had to be convinced that this was happening.”

Noel also worked with the College Commitment Program (CCP), which helped recruit students to San Jose State who otherwise may not have had a pathway to college. He reunited with his sweetheart Mary East, who had come to California separately to pursue an education and to mentor black high school students from Los Angeles, Oakland and Richmond. Also in 1967, university funds were allocated for the Educational Opportunity Program (EOP), a recruitment and retention program designed to support incoming black and Chicano students. The CCP was assigned an advisor, Psychology Professor Robert Witte, and given an office.

Noel and Edwards saw that black student-athletes had a platform that could be used to spotlight civil rights issues. What better way for athletes to elevate the conversation about civil rights than by boycotting the 1968 Olympics? By bringing together Tommie Smith, ’69 Social Science, ’05 Honorary Doctorate, Lee Evans, ’70 Physical Education and Edwards’ brother James, Edwards and Noel formed the Olympic Committee for Human Rights, the organizing body that later formed the Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR). Among those who volunteered to support the OPHR were four women: Noel’s future wife East, ’99 MA Education, Educational Administration Credential, Sandra Boze Edwards, ’70 Social Science, Teaching Credential, ’88 MA Education, Gayle Boze Knowles and Rochelle Duff Davis, ’71 Social Science.

The OPHR protested human rights violations committed against blacks in the U.S., exposed the exploitation of black athletes as “political propaganda tools” and set four conditions for the International Olympic Committee (IOC): uninvite South Africa and Rhodesia, which had white minority rule at the time; restore Muhammad Ali’s boxing title; remove Avery Brundage as president of the IOC; and hire more African-American coaches. OPHR members created an international platform to discuss and address these cultural, political, social and economic needs.

“Harry developed the ideas and theories that we would pursue and communicate with the media,” says Noel. “My role was to serve athlete needs—convince them to join the OPHR and resolve any fears they might have about becoming radical people. I worked a lot with Tommie Smith and Lee Evans, who were involved directly with other athletes. They were the boots on the ground.”

Noel understood that because the OPHR challenged the racial, economic and political status quo under the glow of an international spotlight, it came with great risk. Though there was no official boycott, it was understood that OPHR members would stage a demonstration in Mexico City. Watching Smith and Carlos raise their fists on the Olympic podium after that fateful 200-meter race, Noel was struck by the message they sent to the world and to their compatriots.

“What Smith and Carlos did was jaw-dropping,” he says. “Totally iconic.”

Fifty years later, Noel recalls how he felt watching the movement he helped create send a ripple effect across the globe. His words are careful, quiet; his eyes misty. For him, sport offered entry to college and provided a platform to advocate for humanity—to defy Jim Crow, to generate productive dialogue and thoughtful action, and to inspire the generations that followed.

A great article on a great person. I just knew him as a great runner in his senior years.