Young Adult Literature—Not Just Entertainment

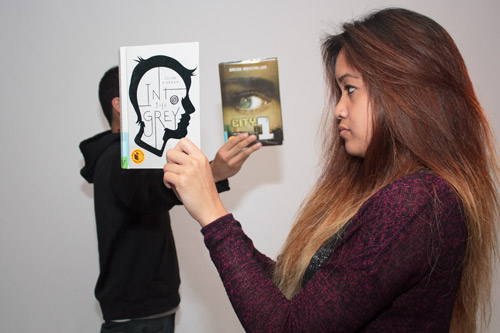

Photo: Muhamed Causevic, ’15 Graphic Design

J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series, beginning with The Sorcerer’s Stone in the late 1990s, ushered in a new era of appreciation for Young Adult literature—literature written for teens 13 to 18. In 2015, it’s an established fact within publishing circles: YA novels attract more readers, more booksellers, more editors and more literary agents than ever before. But even before Rowling’s Harry cast his spell on readers, authors such as S.E. Hinton (The Outsiders, 1967), Judy Blume (Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret, 1970) and Robert Cormier (The Chocolate War, 1974) were penning novels destined to become YA classics.

For her take on the genre, its appeal and evolution, WSQ checked in with Professor Mary Warner, Department of English, who teaches a course on YA literature and is the author of Adolescents in the Search for Meaning: Tapping the Powerful Resource of Story.

For her take on the genre, its appeal and evolution, WSQ checked in with Professor Mary Warner, Department of English, who teaches a course on YA literature and is the author of Adolescents in the Search for Meaning: Tapping the Powerful Resource of Story.

Even among experts, there seems to be some debate about what constitutes YA literature. How do you define it?

Warner: A rather arbitrary part of the definition of YA literature is that the protagonist(s) are thirteen-years-old and up. (This distinguishes YA literature from children’s literature where the protagonists are infants to age 12.) While YA literature addresses teen readers, the best works embody complex literary devices and universal themes found in canonical texts and other adult literature. Social issues such as death, religion, politics, race, economics and sexuality are common themes that YA literature tackles. In their development into adults, teens are establishing their identity, forming relationships and expanding their perspectives. Thus, they want to read books that speak to these issues.

Professor Barbara Bontempo of Buffalo State has said: “Young readers want a hero.” Do you agree?

Warner: Actually this statement could be made about readers of any age. One of the great archetypes of literature is the hero—the figure who will stand up for what is right and champion that good will triumph over evil. Typically YA authors create the contexts for their teen protagonists to be heroic following a characteristic colloquially described as “Please, Mother, I want the credit!” They devise ways for the characters to solve problems and achieve worthy accomplishments. Harry Potter exemplifies this pattern, as do, among others, Liesel Meminger in The Book Thief, Jonas in The Giver and Lily Owen in The Secret Life of Bees.

YA books seem to have fewer “happy-ever-after” endings than books written for pre-teen readers. Why do you think that’s the case?

Warner: Teens are closer to adulthood and to the issues adults face. They need guides to help deal with all that is not “happy-ever-after.” YA books are basically optimistic, with characters making worthy accomplishments. At the same time, the YA authors writing contemporary realistic fiction, sometimes called “the problem novel genre,” suggest that young adults will have a better chance to be happy if they have realistic expectations about both the good and the bad in our world. Through fiction, readers learn about characters and how they deal with life’s challenges from a safe and neutral distance where the danger does not threaten.

Are there other common denominators to be found in successful YA literature?

Warner: Young adults need story—story with which they connect. Marion Dane Bauer, editor of Am I Blue?, a collection of short stories that focuses on adolescents and sexual identity, shares a powerful statement: “I have never met a bigot who was a reader as a child.” Successful YA lit takes readers beyond the barriers of “unknown” or “different.” As an adult reader of YA lit, I find the best YA books transport me to other worlds. I’m “with” the characters in their confrontations with loss, death, pain, loneliness and violence, and in the joys of friendship, love, adventure and success. The appeal of the best YA lit is to be life-changing and, at times, life-saving, giving readers connections to others’ stories.

Has YA literature significantly changed since the 1960s?

Warner: YA literature has adapted to the changing realities of the decades since the 1960s. YA literature of the ’90s and the first decade of the 21st century has become “grittier” and “edgier” in language, topics and genres. Nancy Garden’s Annie on My Mind, a groundbreaking lesbian/gay relationship book in 1982, has been succeeded by multiple LGBT books that are powerful books dealing with gender issues. The flood of dystopia, science fiction and steam punk novels mirror sociological and technological advancements. Graphic novels and other books with variant textual presentations capture some of the effects of texting and multimedia. The paranormal and Gothic have grown in popularity, and fantasy from Kristin Cashore, Tamore Pierce, Philip Pullman and Diana Wynne Jones (and of course J. K. Rowling) dominates the best reads lists. A significant change is also the representation of cultures and ethnic groups—Naomi Shihab Nye and Suzanne Fisher Staples offer pictures of the Middle East; My Forbidden Face, by Latifa, chronicles a young woman’s life under the Taliban.

In your SJSU class, Literature for Young Adults, students are asked to list books they read as adolescents that significantly impacted their lives. What are some of their favorites?

Warner: I ask my students in the first class meeting to name a favorite book or literacy practice from their childhood and explain why this book or literacy practice is important. Among the literacy practices students have talked about: moms taking them to the library, grandmothers sharing stories of their childhood, and parents reading to them. It’s key to celebrate the ways parents and other significant adults can foster and support reading early on. The books’ names range from Charlotte’s Web, Where the Sidewalk Ends, Where the Wild Things Are and The Cat in the Hat to The Chronicles of Narnia, The Giver, The Harry Potter series, Hatchet (Gary Paulsen) and Holes (Louis Sachar). As young people move through middle school into high school and their interest in reading wanes, it becomes even more important for teachers and significant adults to simply suggest: “This is a book you might like.”

As a literacy specialist, you’ve expressed concern about an “aliterate” trend among students. Can YA literature help reverse that trend?

Warner: Reading and writing are integrated literacies and each supports the other. These literacies can only become stronger when we read and write often, when we build our reading and writing muscles. Unlike illiteracy that refers to those who are unable to read, aliteracy means that one is able to read but chooses not to. I use an activity called a “book pass” to help my students see as many YA books as possible. I bring to class about 100 YA books, and students are given one to two minutes to quickly review the book. They make lists of the books they’d like to read—those that capture their interest in some way. YA lit can reverse the trend toward aliteracy in providing reading that is accessible and with which teens can connect and in which they can find pleasure.

Any predictions regarding YA’s future?

Warner: YA authors want to keep connecting to teen readers; they want to keep addressing what is significant in teens’ lives and experiences. I am a reviewer for two major journals in the field of YA literature, and several of the books I’ve reviewed in the last year are examples of YA authors creating what they believe to be relevant. City 1: (Revolution 19) describes the “Bot” controlled world in the 2040s. In the sterile world of robots and automation, the teens’ quest to save their parents and other family members poignantly emphasizes the importance of humanity/humanness, giving the novel universality that surpasses that of typical science fiction/apocalyptic, technological world war stories. Another example is Into the Grey. The book is set in Ireland in the ’70s and poignantly captures the fierce loyalty of brothers, living and dead.

Your personal all-time favorite YA novel?

Warner: It’s very hard to narrow down to an all-time favorite YA novel. A book that I have taught often and reread every time I’ve taught it is Witness by Karen Hesse. It is actually a free verse poem, written in five acts. Additionally, it’s historical fiction, inspired by the true story of a Ku Klux Klan incident that took place in Vermont in the 1920s. In Witness, eleven characters share the story through vignettes that are witty, satirical and profound. Leanora Sutter, a 12-year-old African American girl, harassed by an older classmate who tells her the “dragons talked about lighting you and your daddy up…,” says she turned her back and walked out of the school, “without my coat,/without my hat or rubbers./I didn’t feel the cold,/I was that scorched.” In class, we read the book aloud with students assuming the roles of the eleven citizens. Every time, I’m amazed at how well the students “get” the characters and voice them as they read. Afterwards we write about a shared experience in our lives. I frequently use the events of September 11, 2001. Mirroring Hesse’s vignette style, students are encouraged to write about their own experiences or in the voice of someone they select (e.g., first responders, passengers on the flights, those working in the Towers). Then we read aloud and create our own readers’ theatre. Read examples online.

So amazing