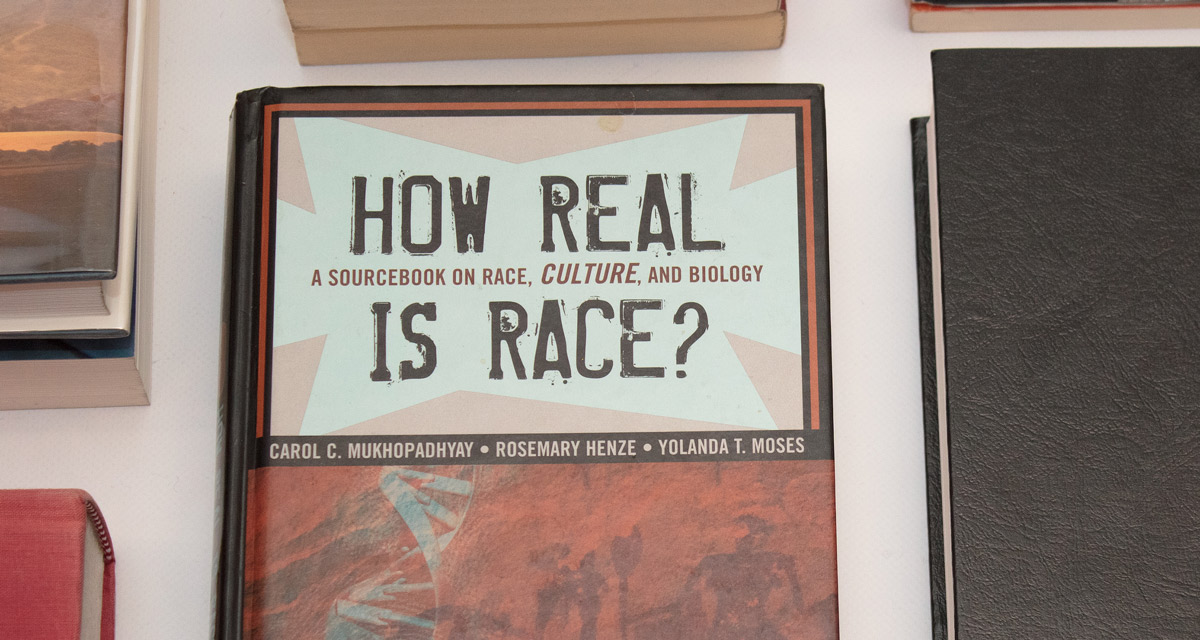

Book Talk with the Authors of How Real is Race?

Photo: Muhamed Causevic, ’15 Graphic Design

In How Real Is Race? (Rowman and Littlefield, 2014), Anthropology Professor Emerita Carol Mukhopadhyay and Linguistics Professor Rosemary Henze, along with co-author Yolanda Moses, anthropology professor at UC Riverside, dissect the complex and often controversial concept of race using an anthropological approach.

In How Real Is Race? (Rowman and Littlefield, 2014), Anthropology Professor Emerita Carol Mukhopadhyay and Linguistics Professor Rosemary Henze, along with co-author Yolanda Moses, anthropology professor at UC Riverside, dissect the complex and often controversial concept of race using an anthropological approach.

What is the true definition of race and how does your book help clarify that definition?

Henze and Mukhopadhyay: Race is a culturally invented concept, not a scientific description of biological reality. As such, and as with any socially constructed concept, there is no “true” definition of race. Race is a way of describing social groups in the U.S. and some other parts of the world. But there are many definitions, and each tends to emphasize some dimensions of race while downplaying others. In our book, we emphasize that although race is a biological fiction, it is nonetheless a deeply engrained social reality. The U.S. system of racial classification, in particular, is a historically and culturally specific way of explaining, justifying and perpetuating a system of social, economic and political inequality. Race and racial classifications are still today used to uphold the power and privilege of some (mainly European American, Christian middle- and upper-class males) at the expense of those who are racialized minorities. Race may be biological fiction, but the social ideology of race has real consequences for people’s lives.

What we try to do in the book is to shed light on precisely how and why race is unreal in the biological sense and yet very real in the social, ideological sense. Our hope is that by providing a more nuanced and evidence-based explanation, the subject of race itself, which has been largely avoided in public discourse, as well as in educational curricula and cultural diversity forums, can become part of and strengthen existing pedagogies of race and anti-racism.

How does your anthropological approach differ from previous approaches?

Henze and Mukhopadhyay: Most conventional approaches to race take either a biological or a social constructionist approach. The biological approach analyzes race from a genetic and evolutionary perspective, focusing on why the concept of “race” is not a scientifically accurate or meaningful description of human biological variation. The social constructionist approach emphasizes the idea of race as a social, cultural and historically specific “construction” or invention, created to legitimize and reproduce social inequality. Biology is usually ignored or seen as irrelevant.

Our book takes an integrated, biocultural perspective, arguing that both approaches are necessary if we are to understand how race functions in the past and the present. We must understand how biological markers, such as skin color, and social controls over mating, such as anti-miscegenation laws, have been used to create and maintain the culturally invented but powerful and “real” social divisions we call “race.” Our anthropological approach also incorporates a cross-cultural perspective on race.

How can educators better “frame the conversation” when discussing the topic of race in the classroom?

Henze and Mukhopadhyay: Before educators can figure out how to frame the conversation, they need to make a commitment to discuss it in the first place. Many educators avoid the topic because their academic or teacher education programs have not prepared them well to deal with the topic. In addition, many of us are fearful of opening up volatile conversations, fearful of being called a racist, fearful of setting off emotions we don’t know how to channel into a learning opportunity.

As with other subjects, a good place to begin is with students’ own questions. What confuses them about race? What questions do people ask them about race and how do they answer? These questions can be archived as touchstones for the class to come back to after further study. Throughout the process of delving into the scholarly research on race, educators need to make sure that the classroom is a “safe space” for students to speak and be heard. Educators are also racialized persons and need to acknowledge how their backgrounds have afforded or obstructed particular experiences and opportunities in life. And we shouldn’t forget that identity is very complex; other dimensions such as gender, class, sexuality, religion, language, etc., all intersect with our racial identity.

Any serious study of race and racism must consider the structural nature of racial oppression in the U.S. and other countries. The task is to understand how we ended up with a racially oppressive system, how this system has morphed over time, and how we can best insert ourselves into the continuing project of undoing racism both at the structural/institutional and cultural/interpersonal levels. Ultimately, why study race and racism if it isn’t to end the systematic oppression we call racism?

Did your research turn up any unexpected or surprising results?

Henze and Mukhopadhyay: Our review of the research, especially on human biological variation, produced even more evidence that skin color and other traditional “markers” of race in the U.S. are incredibly superficial, biologically meaningless and a miniscule fraction of the amount of biological variability that exists within any single human being and in the human species as a whole.

Our research also revealed the unstable, shifting, strategically motivated nature of U.S. racial classifications and U.S. immigration laws. We were also struck by the recurring parallels in the negative stereotypes that dominant Euro-American elites used to describe subordinate ethnic groups, even as the specific group changed over time. Finally, our research revealed how under-studied are the gender and sexual dimensions of race and ethnicity, especially the ways in which society and laws have been used to control mating and marriage, generally, and female sexuality, specifically.

In 2015, are we, as a society, less or more “race conscious” than we were 20 years ago?

Henze: Twenty years ago seems like a relatively short time to consider this question. But I think, at least in the U.S., we have been moving away from the more explicit, legally sanctioned forms of racism that existed in the time of slavery, and afterwards under Jim Crow and anti-miscegenation laws. But does the end of legally sanctioned institutional racism mean that we are less race conscious? I don’t think so. It just means that race consciousness has gone underground and is therefore harder to track.

We continue to be “race conscious” in the sense that most of us still think of the social world in terms of race, but we are a little less likely to use racial terms, perhaps, to describe that way of thinking. Our language has become more covert. Instead of asking about the racial demographics of a college, we ask how diverse the college is, and instead of having workshops on anti-racism, we “celebrate diversity” and practice “inclusive excellence.” But this is not to say we aren’t making progress. Recent generations are challenging taken-for-granted categories and publically exposing the complex identities that racial classifications ignore. We are slowly coming to terms with racism, but it will take a long time, and pretending that it has gone the way of the dinosaurs isn’t going to help.

Mukhopadhyay: I think 50 years is a better time frame—or going back to the ending of legal segregation, whether in schools or other public facilities. Having been alive during that entire period, I see the tremendous advances that have been made. In a sense, in the 1950s, Euro-Americans were both race-conscious and not race-conscious. Many Euro-Americans were so subconsciously accepting of race and racism that we didn’t even notice how racially segregated our lives were.

In contrast, in the 1960s and 70s and even 80s, the vast majority of our society, especially Euro-Americans, became very race-conscious. These decades of “consciousness” did, I think, help us accomplish the relatively “easy” tasks of eradicating the most explicit, formal, institutionalized racism (e.g., legally segregated schools, explicitly racist hiring practices). Now, we’re confronted with the more subtle aspects, including the degree to which race intersects with economic inequality, intrinsic to our capitalist economic structure; with sexism and cultural concepts of masculinity (and femininity); with micro-cultural and ethnic religious-based cultures. Moreover, our U.S. population has become much more diverse, challenging old, simplistic, racial black-white dichotomies. So, in some ways, we are more conscious because the prototypic “white,” or European-American is, increasingly, a minority. Perhaps, most profoundly, racism is no longer publicly acceptable and officially legitimized and defended.

What are the advantages of teaching at SJSU?

Henze and Mukhopadhyay: What makes us proud to be on the faculty here is the fact that our students come from all kinds of families, from all economic strata, from all kinds of ethnic and racial backgrounds, nationalities, religions, language groups, sexualities and, of course, genders. We are not an elite-serving institution, and we hope that we don’t become one (despite economic pressures that are making an SJSU education harder to attain for working class students).

We feel proud when we tell people that many of our students are the first in their families to attend college. By teaching here, we get to be part of the process of making higher education attainable for students who, a few generations ago, would not have had that opportunity. We get to play a role in expanding both their opportunities and horizons. And we get to share in the enthusiasm they bring with them into the classroom and campus.