Addressing Food Insecurity Among Students

“Food insecurities are affecting students, and action is happening all over the country. I really hope this university continues to take great steps toward finding a solution, and that students understand that there are already great resources on this campus to help those who are struggling.”—LooLoo Amante, Associated Students President Elect 2015-16. (Photo: Thomas Sanders, ’14 MFA Photography)

Before the start of the fall 2013 semester, LooLoo Amante was in a good place. She had spent the summer at home in Southern California doing a paid internship with NBCUniversal. With her earnings, Amante, ’16 Advertising, bought her first car, which she used to head north early to kick off her second season with the Spartans cross country team. Her plans for more affordable off-campus housing hadn’t quite solidified yet but she was confident that they would. Amante was content to be figuring it out as she went. “It was a really exciting time in my life. The thing is,” she says, “I wasn’t really eating.”

Plans fell through, money ran short and, almost without realizing it, Amante had become one of the estimated several million college students struggling with hunger issues nationwide—including at San Jose State.

This is not about living on dreams and Top Ramen. The USDA defines food insecurity as “consistent access to adequate food limited by a lack of money and other resources at times during the year.” It has been associated with decreased concentration and energy, depression, stress and poor health—all of which are linked to lower GPAs. Factors such as the rising cost of education and textbooks, the affordable housing crisis, increased college enrollment among students from low-income families and changing federal loan policies have brought this issue to college campuses across the country.

In 2012, a Student Health Center survey of 2,260 SJSU students found that more than 30 percent sometimes or often felt hungry and did not eat because they couldn’t afford to purchase food. These results led to the formation of the SJSU Student Hunger Committee. Tova Feldmanstern, a clinical social worker in Counseling and Psychological Services, spearheads the group of students and staff and faculty members. Their goal: to find solutions for food insecurity at SJSU.

“The first survey was so small,” says Stephanie Fabian, ’08 Advertising, committee member and assistant director of marketing and communications for Spartan Shops. “We wanted more data.” A second, more comprehensive survey was sent out to the entire student body via email in 2014. It confirmed what the first survey suggested. Of about 5,000 respondents, 39 percent said they had sometimes or often skipped meals while hungry because they didn’t have money for food. The committee believes the responses are representative of the campus as a whole.

Kristen Wonder, ’15 Environmental Studies, is the sustainability coordinator for Spartan Shops and assists with the committee. A transfer student, she dealt with her own hunger issues while in community college. “If you’re food insecure, you have a lot of stuff going on in your life,” she points out. “You’re probably really busy trying to survive.”

A first-generation American, college student, high school graduate and even the first driver in her family, Amante was barely surviving with two campus work-study jobs and financial aid for tuition. “If I had money I would buy something cheap,” she says. “But mainly it was about how long I could make a burger last and what event on campus was offering free pizza.” Some days, all she would eat was a granola bar bummed from a fellow athlete in the locker room, despite her grueling cross country runs. She began suffering from headaches and fatigue. “It took a toll,” she says. “There was always that question: Should I be in college right now?”

There are now more than ten food cupboards—small, informal pantries—on campus where any student can walk in and grab food, no questions asked. (Photo: Muhamed Causevic, ’15 BFA Graphic Design)

“This is a real issue,” says Fabian. “In order to aid our students with their academic success, we need to help them eat.”

The 2014 Hunger in America report from Feeding America, a network of about 46,000 emergency food service agencies, estimates that roughly 10 percent of its 46.5 million adult clients are currently students. Of more than 60,000 clients surveyed, Feeding America reports that nearly one-third have had to choose between paying for food and covering educational expenses at some point in the last year. In the last decade, more than 100 on-campus food pantries have opened across the country, according to the College and University Food Bank Alliance.

Led by the hunger committee, SJSU is following suit. Since launching a website with information about food resources, CalFresh benefits and educational materials, the committee has turned its attention to developing on-campus emergency food resources. Committee members from Spartan Shops and Associated Students have been leading successful non-perishable food collection campaigns—and students are donating almost all food items.

“Our student employees are very supportive of this cause,” says Fabian. “Some of them have said, ‘I wish I had known about this sooner because I dealt with hunger, or my friend is dealing with hunger.’”

There are now more than ten food cupboards—small, informal pantries—on campus where any student can walk in and grab food, no questions asked. The committee is working with specific departments to host their own cupboards.

“If a department has a bookshelf or a table, we bring a box of goods to get it going,” says Fabian. “We will restock, too, but we encourage faculty and staff members to collect food to demonstrate their support for their students.” While there is no registration process, the committee knows students are using them, as the pantries constantly require restocking.

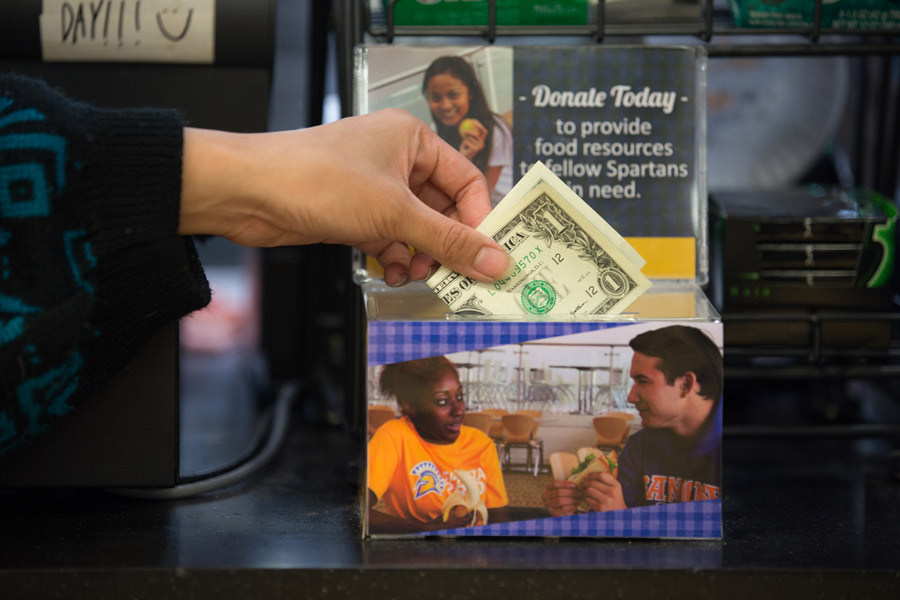

Find change collection boxes in on-campus eateries. Donations provide food resources to fellow Spartans in need. (Photo: Muhamed Causevic, ’15 BFA Graphic Design)

One of the committee’s goals is to garner institutional support, namely space and funding, for a campus food pantry, similar to those on many other campuses, that would offer a variety of healthy food options for students beyond what a bookshelf of non-perishables can provide. There are fundraising efforts involved as well, including change collection boxes in on-campus eateries. People are being generous, says committee member Robb Drury, associate vice president for advancement operations, who estimates that the change boxes are bringing in about $500 per month. The generosity is evidenced through online donations, too—several thousand dollars worth of pledges have been made to the account through the SJSU online giving website early this year.

By the spring 2014 semester, Amante was back on her feet, due in large part of the efforts of Feldmanstern, who helped identify her issues and secure CalFresh benefits.

“When I see Tova now, I get nostalgic,” says Amante. “Like, oh my gosh, last year I was couch hopping and hungry. Now I’m in a place where I feel grounded and stable.”

She might add ‘thriving.’ Amante maintains a 3.4 GPA, serves as AS director of external affairs and recently won the election for AS president for the 2015-16 academic year.

“Ultimately, I see my experience as being a part of something bigger,” she says. “Food insecurities are affecting students, and action is happening all over the country. I really hope this university continues to take great steps toward finding a solution, and that students understand that there are already great resources on this campus to help those who are struggling.”