Amanda Kahn Likes to Be in the Octopus’s Garden

Deep below the ocean’s surface just off the Central California coast, thousands of octopus gather near an extinct underwater volcano. Video and photo on previous page courtesy of MBARI.

Amanda Kahn, ’10 MS Marine Science, assistant professor of invertebrate ecology, has a long-standing fascination with marine science, exploration and the deep sea. Her enthusiasm is infectious even over Zoom. While her usual focus is on the ecophysiology of sponges, she’s quick to reassure that she also finds octopus “extremely interesting.” So she was delighted to be a part of the expedition that helped discover a deep-sea octopus nursery off the California coast.

How did a sponge specialist end up stumbling upon the Octopus Garden? Simple: through one of those wonderful, strange accidents of science. In 2018, Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary scientists invited Kahn out onto the E/V Nautilus ship as part of their research explorations of Davidson Seamount, an underwater mountain 80 miles off the coast of Monterey. She was searching for sponges, which were known to be at the summit.

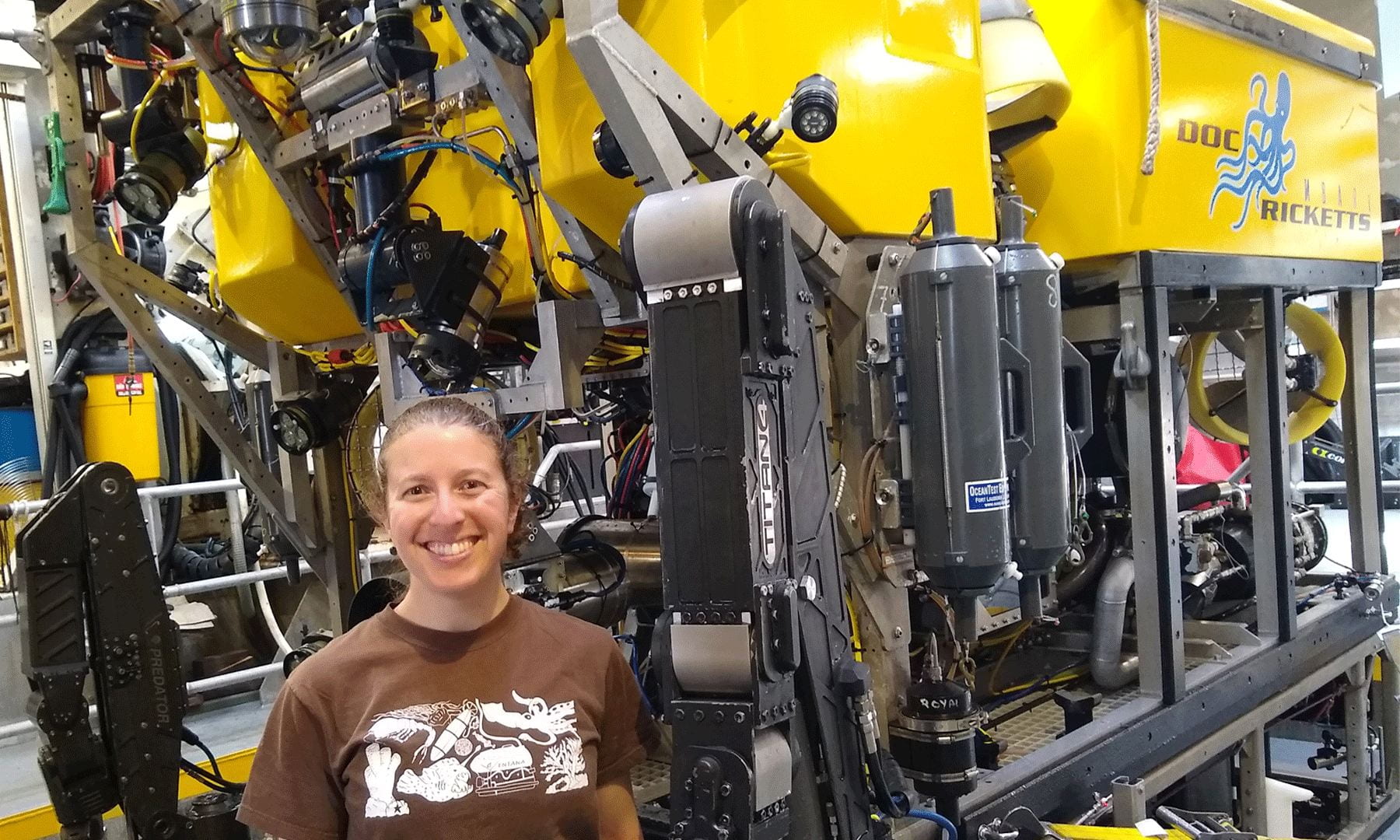

Amanda Kahn onboard MBARI’s R/V Western Flyer in front of the remotely operated vehicle Doc Ricketts. Photo courtesy of Amanda Kahn/MBARI.

So there she was, sitting in the control room alongside scientists and crew, livestreaming the feed from a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) operating two and a half miles below the surface as it explored the deep sea.

First they spotted a pearl octopus – a rare sight, since they’re hard to detect and solitary. They followed it, and that led them to an even rarer sight: a shimmer and what Kahn describes as “strings and strings” of octopus, like beads on a pearl necklace. They drew the ROV closer and soon discovered that many of the octopus were upside down, brooding over eggs in nests.

And that was it: they had discovered the Octopus Garden. “Everybody on the ship just gasped together,” Kahn remembers. “We were beaming.”

A Deep-Sea Sensor

That was 2018, the beginning of many years of research and various expeditions to the Octopus Garden. Kahn was a postdoctoral fellow at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) at the time. After that first cruise, her postdoctoral advisor MBARI Senior Scientist Jim Barry assembled a large team of experts from a variety of institutions and fields, including Kahn, to study what was going on. MBARI and collaborators visited the Octopus Garden 14 times over the course of three years to learn why so many octopus gathered at this site.

“I was instantly curious what was attracting all of the octopus to this area and what all the interactions were that were happening between the octopus and their environments and the other life that’s there,” Kahn says. Her work on the metabolism of sponges, who as filter feeders provide a great deal of nutrients to animals living in the desert of the deep sea, focuses on similar questions.

MBARI engineers had previously developed a deep-sea temperature and oxygen sensor so that Kahn could study metabolism in sponges. MBARI researchers used this same sensor on subsequent dives to the Octopus Garden to “gently put the probe inside the octopus nests and measure the water temperature and oxygen conditions that the eggs were experiencing.”

That led to another crucial discovery: the shimmer the Nautilus Live team had previously seen, similar to heat coming off asphalt, was warm water seeping up from the rocks. This heat helped the eggs hatch faster, speeding up the brooding period from the expected five to eight years down to a little less than two years on average, “therefore increasing the chances that the young would hatch and survive.”

The Perfect Nursery

As it turns out, temperature is crucial for octopus development. Octopus mothers are extremely dedicated, and often reach out to provide a helping hand (and hand and hand and hand and hand and hand and hand and hand) to their young. The mothers lay their eggs, sit on their nests and subsist only on the resources they have remaining – for all the time they brood, they don’t eat, and they die after the eggs have hatched. Like lizards, octopus are ectotherms, or cold-blooded. If the water temperature is colder, their metabolic rate will be slower, and they’re slower as a result. If it’s warmer, their metabolic rate will be faster, which helps speed up hatching.

But this is a dangerous game – as Kahn explains, another octopus nursery was previously discovered off of Costa Rica under similar circumstances, near warm water, where several mothers had gone to brood. But in this one, none of the eggs were viable. Scientists hypothesized that in this case, the water may have been too warm, “beyond the thermal tolerance of the eggs,” as Kahn says, or the mothers may have died too early, leaving the eggs to hatch without any defenders.

In a way, this makes the Octopus Garden off Central California something of a Goldilocks situation – at least for now, many eggs have hatched. Observations suggest this is a stable nursery, benefiting not only pearl octopus mothers but also the community of life that thrives alongside the octopus. MBARI scientists, who have watched over the Octopus Garden for three years, can recognize individual octopus from their scars. They were able to track the mothers, watch them brood over their eggs and then watch those eggs hatch. (Whether the hatched octopus survive to adulthood is another question, however – hungry shrimp and anemones grab at those that try to leave the nest.)

Ongoing Discoveries

The researchers’ continuing discoveries have had many other unexpected, even delightful consequences. Besides the actual moment of discovery, Kahn says one of her favorite parts of the whole experience has been classroom outreach. She’s participated in discussions led by the Ocean Exploration Trust from the exploration vessel Nautilus, where she talks to students ranging from elementary to community college-age about what’s going on underneath her feet.

“The deep sea is the biggest habitat that we have in the world,” she says. “I really love going out and exploring somewhere on our planet that we really know so little about.”

And the research implications of MBARI’s work, recently published in the journal “Science Advances,” could be wide-ranging. For one thing, the question of conservation: Luckily, Davidson Seamount is already protected as part of NOAA’s Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary. But as Kahn states, “This was an accidental serendipitous discovery, and we don’t know how many other of these localized hotspots are out there.” Some of these hotspots could be jeopardized by deep-sea fishing or mining, naturally leading to questions of environmental protections and stewardship.

For another, survival in the deep sea carries great difficulties, since food sources are few and far between. And hotspots like the Octopus Garden are brimming with food, which is to say brimming with life – oases of life in the deep-sea desert. These food webs fascinate Kahn and many others, and may lead to even more extraordinary scientific discoveries.

So the research cruises to the Octopus Garden continue, as they have since that first fateful day. Kahn is so grateful to have been involved; Her enthusiasm for the collaboration is tied to her enthusiasm for science as a whole.

“I love just how beautifully the different fields all fit together to build this story,” she concludes. “This shows so much of the scientific process: you discover and develop questions, and a team answers those questions, following where the science leads.”

Learn more about Amanda Kahn’s sponge expertise in this “Accidental Geographer” podcast episode.