Duane “Michael” Cheers: Sharing the Legacy of W.E.B. Du Bois

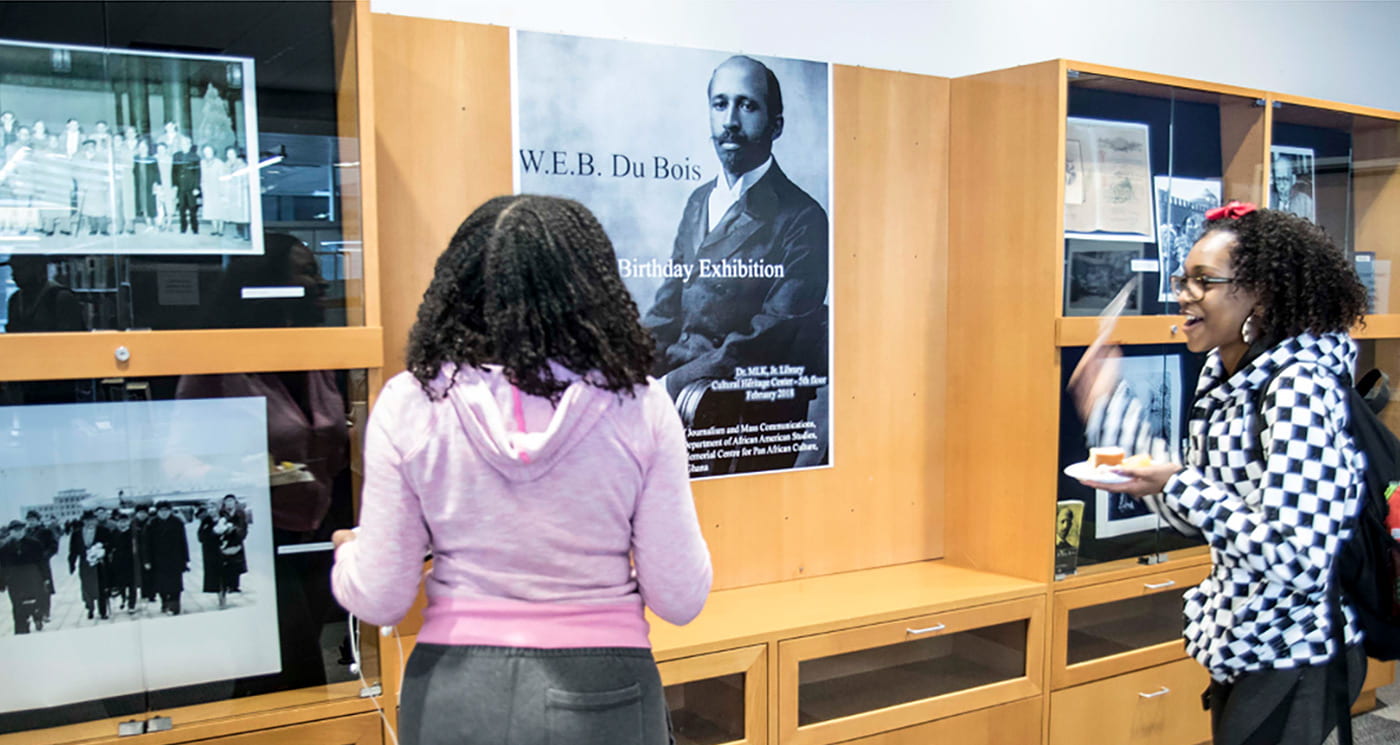

The W.E.B. Du Bois exhibit at the Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Library. Photo courtesy of Michael Cheers.

“I realized I could stand on the sidelines and complain, or become a partner in educating this generation of students.”

Associate Professor of Journalism Duane “Michael” Cheers says studying African-American history “has been part of my DNA since childhood.” The great-grandson of slaves became immersed in the story of W.E.B. Du Bois, the first African-American to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard University and a co-founder of the NAACP, in the late 1970s and early 80s while studying for a dual master’s in African-American studies and journalism at Boston University. Cheers is now working to digitally preserve damaged photographs and personal documents belonging to the sociologist, civil rights activist and historian.

“During my 1978 summer internship at Ebony and Jet magazines in Chicago, I shadowed the editors who were finishing their edits and layout on Du Bois: A Pictorial Biography, by Shirley Graham Du Bois, his second wife,” Cheers says, noting he has “been re-reading, researching and studying Du Bois” in the decades since. “I’m also probably the only African-American professor at San Jose State who owns a first edition The Souls of Black Folk, first published in 1903.”

In 1993, Cheers traveled to Dakar, Senegal in West Africa for National Geographic Television, filming his experience as a descendant of slaves, spending the night in a slave dungeon on Goree Island for a mini-documentary that aired on the channel. “That experience was also rooted in my reading of Du Bois’ book, The World and Africa: An Inquiry Into the Part Which Africa has Played in World History, where the father of Pan-Africanism hauntedly discussed the horrors of the slave trade,” says Cheers.

Associate Professor of Journalism Duane “Michael” Cheers in Ghana. Photo courtesy of Michael Cheers.

Staff members at the Du Bois Centre in Accra, Ghana, install the W.E.B Du Bois 150th Birthday Tribute exhibit inside the home where Du Bois lived from 1961-1963. The display was originally at the Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Library in 2018. Photo courtesy of Michael Cheers.

During a 2016 visit to the Du Bois Centre for Pan African Culture in Accra, Ghana, Cheers noticed the materials Du Bois brought with him to Ghana in the 1960s and stored in the home where he died in 1963 were neglected and had been eaten away by ants and termites, and deteriorated by poor climate control.

“I noticed that the Du Bois photographs, papers, documents and scrapbooks from his trips to Russia and China were deteriorating,” Cheers says. Upon his return to San Jose, he emailed the institute to ask if they’d allow him to scan and digitize the materials, which he acknowledged would be a “monumental” project. They consented and the project began.

Cheers contacted Tracy Elliott, dean of the Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Library, suggesting the digitized Du Bois materials could become part of the digital archives of the library’s Africana Collection. Cheers is also collaborating with librarian Kathryn Blackmer Reyes, director of SJSU’s Africana, Asian American, Chicano and Native American Studies Center. Elliott lent him a high-resolution scanner and Cheers and his daughter, Imani, assistant professor of media and public affairs at George Washington University, each applied for grants and have teamed up on the project, which has involved hundreds of hours of scanning.

“We scanned close to 1,000 documents in Ghana—photographs, papers, diaries—everything they had,” Cheers says. He also located some VHS tapes from the 1980s in a basement crawl space at the Du Bois Centre and has been working with SJSU Media Producer Keith Sanders to digitize as many of the frail videos as possible. To date, “two really important” videos of Du Bois’ 1963 funeral and the 1985 opening of the centre, when Maya Angelou was a keynote speaker, have been rescued, and are expected to be part of Cheers’ planned documentary that looks at the final two years of Du Bois’ life, when he was working on an encyclopedia.

A memorandum of understanding between the Du Bois Centre and King Library to house the digital archive at SJSU is in the works, “making it available, free to students, scholars and researchers around the world,” Cheers says. “I feel this material should be available to the public.”

Students enjoying the W.E.B. Du Bois exhibit at Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Library. Photo courtesy of Michael Cheers.

Cheers in 2018 curated the 150th birthday tribute to Du Bois on the fifth floor of King Library, featuring Du Bois’ materials and videos. “I was annoyed by how few students knew of Du Bois and his contributions to African-American history,” Cheers says. “I realized I could stand on the sidelines and complain, or become a partner in educating this generation of students.”

While Harvard and the University of Massachusetts-Amherst have digital collections of Du Bois’ works, Cheers has scanned, digitized and archived photos and documents those universities don’t have.

“Hopefully, our campus library’s Africana Collection will become a repository of this material, and professors at SJSU will include Du Bois in their lesson plans,” Cheers says.

Cheers is scheduled to return to Ghana this summer to check on the progress of renovations at the Du Bois Centre and get measurements so he can return later this year or early next year to set up his display and bring the exhibit to Ghana once the institute’s renovation is complete.