More Than Marches

SJSU is using education as a catalyst for social change—on campus and beyond.

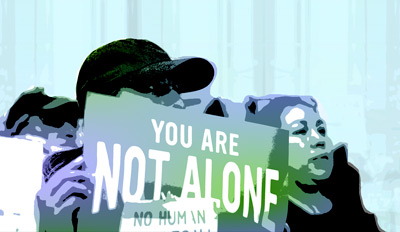

Photos of SJSU protests by James Tensuan

It was 1964 and the Rycengas had just moved to the Northeast when a stranger knocked on their door, pushed a petition into Jennifer Rycenga’s father’s hands, and encouraged him to sign it, saying it would keep “undesirables” out of their suburban neighborhood. Rycenga, who was six years old at the time, recalls her usually placid father exploding in rage at this prejudiced man trying to institute some racial code.

Photos of SJSU protests by James Tensuan

“As I grew up and understood his anger, I have grown more and more proud of his stance at that moment,” says Rycenga.

Fifty plus years later, her father’s example continues to galvanize her to speak out against racism, only instead of doing so from a front porch, the professor of comparative religious studies attempts to address inequalities in the classroom at San José State. Her research demonstrates that a lot of movements in history have restricted access to education because it can be a tool for social change, particularly in the lives of young people, and she actively shares these discoveries with students.

Now in the era of #MeToo, #BlackLivesMatter, #TimesUp and #NeverAgain, when people are attempting to change modern culture from the boardroom to the movie theatre, alumni and faculty members such as Rycenga are uniting behind hashtags and more traditional forms of social activism to create lasting systemic change in the campus community and beyond. Yet this complicated process elicits a sea of questions. How can the workplace be more accommodating to all genders? What will it take to end police brutality and address the fact that African Americans are incarcerated at a much higher rate than whites? How will Hollywood’s culture change? What impact will Parkland High School students have on gun reform?

A classic sociological concept comes to life

This is not the first time individuals in our country have protested inequality, but unlike previous moments in history, social media allows anyone to broadcast information to a wide audience, highlighting perspectives from frequently overlooked points of view. Now when a story of mistreatment at the hands of police hits the mainstream news media, it goes through various micro platforms. The challenge: these platforms are often divided along party lines. A conservative individual might watch Fox News, while a liberal individual might choose to watch MSNBC. “The downside of social media is that it can put us in echo chambers, increasingly reinforcing perspectives we already have,” says Walt Jacobs, dean of SJSU’s College of Social Sciences.

“If we are honest with ourselves, most of the issues that divide us are not starkly differentiated as right-wrong, good-bad or black-white.” —Marianne Lettieri

Despite our ability to be connected 24/7, Facebook, Twitter and Instagram lack physical spaces where true conversation can occur. Jacobs says these modern movements mirror a classical sociological concept—that of the sociological imagination. In 1959, C. Wright Mills coined the term, which states that to understand your personal experiences you must first locate yourself within larger issues such as racism and sexism—even the experience of growing up in a rural or urban area. “All of these things affect who you are as an individual,” says Jacobs, “and you as an individual can affect the greater society.”

Jacobs teaches digital storytelling to help students reflect on their complex cultural experiences and challenge media messages. Students tell a personal story about their lives using their voices, pictures and music; they then share these as videos in the classroom. These stories, he says, are especially powerful when they are from a social justice perspective and illustrate a little-known viewpoint or showcase how a student persevered. In the process, students learn how to be active listeners.

“One of the problems with communication today is that reality TV and politics are teaching us that communication is a zero-sum battle that produces winners and losers, instead of connection, and the ‘winners’ are those who can scream the loudest,” says Jacobs. But in the classroom such purposeful storytelling can generate connections to larger issues—whether or not individuals have experienced such challenges—and impel them to consider how such examples might alter the circumstances of others.

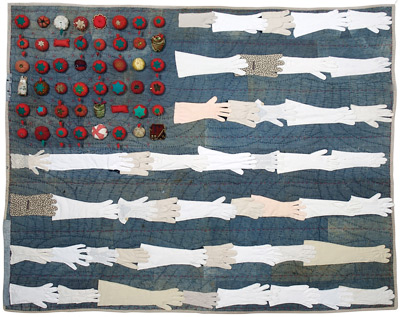

Old Glory: Depression-era utility quilt by Marianne Lettieri

Marianne Lettieri, ’13 MFA Photography, volunteers on the leadership team of Doing Good Well, a nonprofit initiative that teaches next-generation female artists how to use their art to empower change. She has been using her degree from SJSU to draw attention to our culture’s gender divide. “I comb through the offered contents of people’s belongings looking for symbols that reveal shifts in culturally shared values and practices.” One example of this is Old Glory, a utility quilt that re-imagines the American flag with stripes made from denim overalls and overlapping lady’s gloves, much like the ones worn by suffragists; instead of stars, red pincushions dot the blue rectangle. Part of the collection of the San José Museum of Quilts and Textiles, the piece, Lettieri says, underscores the gender inequality that has long plagued our country.

“If we are honest with ourselves, most of the issues that divide us are not starkly differentiated as right-wrong, good-bad or black-white. Art that allows space for personal introspection can bridge the divide that shuts down meaningful dialogue,” says Lettieri. “If a film or artwork can promote gender or racial stereotyping, it can also dismantle it by showing an accurate representation of gender and race.”

Social action through education

Photo by David Schmitz

Rycenga is convinced change begins with young people. “Youths see the world they are about to inherit and they feel its constrictions closing in on them,” she says. “They can choose to put on the chains or break them apart.” Her research on 19th-century abolitionist Prudence Crandall and the academy she opened in 1831 in Canterbury, Connecticut, to educate black women supports this belief. Crandall’s school was one of the “early coalitions across lines of difference in history,” and not only improved the lives of the black women she educated, but advanced the black community by training the women to become teachers.

This sort of ripple effect also prevails at SJSU, where classes such as those with Sociology Professor Scott Myers-Lipton provide opportunities for students to engage with—and create—social change. In Sociology 164: Social Action, students identify issues on campus and in the community that they would like to change and then collaborate on a solution.

“Developing an issue means that you identify a solution to a social problem that you and others in your group feel strongly about and whose goal is specific, simple and winnable, with the result of the campaign being a positive, concrete change for the community,” says Myers-Lipton. Student victories have already occurred thanks to his approach. In 2012, a group of students, the Campus Alliance for Economic Justice (CAFÉ J) led the San José Measure D campaign to raise the minimum wage in San Jose from $8 to $10, and then worked to increase it to $15 by 2019.

This social action curriculum is detailed in his book Change! A Student Guide to Social Action, and the Bonner Foundation has partnered with Myers-Lipton to bring the curriculum to campuses across the country. In fall 2018, five of SJSU’s colleges will use the curriculum, with the goal of having the book used at more than 50 campuses within the next three years. Additionally, Jacobs has charged Myers-Lipton to create a booklet, Social Action: It is in Our DNA, for College of Social Sciences faculty members. Myers-Lipton says the booklet can be “used in their classes to educate students about the social action legacy at SJSU” and provide an overview of social justice events that have occurred on campus.

Moving toward equity

Beyond San Jose, Myers-Lipton believes lasting equity demands an economic bill of rights similar to the one Franklin D. Roosevelt introduced in 1944. “As a result of policy changes in the past 40 years, the U.S has become the leader in the industrialized world in child poverty, income inequality and wealth inequality,” says Myers-Lipton. “The results are antithetical to a democratic society.”

Recent policy changes may lead to more changes in the American culture at large. Dick’s Sporting Goods will no longer sell assault weapons. Big tech companies are developing programs to make the workplace more inclusive for women. This heartens Jacobs. “I am optimistic this change will continue,” he says.

What about groups that might feel that changes to current policies will detract from their lives? “There will always be arguments for both sides,” notes Rycenga. “We cannot be lulled into inaction due to the existence of valid logic for all positions.” She instead encourages individuals to support principles that will help all live the fullest lives they can, rather than meeting the needs of only a few.

“The ability to see and appreciate another’s perspective is the catalyst for societal change and personal growth,” Lettieri adds.

Consider the stranger who turned from the Rycengas’ front porch, clutching his petition. The experience compelled Rycenga to dedicate her career to fighting racism, and this work has had a lasting effect both on her students and those who come in contact with them.

As a result of being exposed to the larger work of social justice, many of Myers-Lipton’s students have chosen to continue fighting inequality. Leila McCabe, ’12 Sociology, says the minimum wage campaign “gave me hope in the political system and allowed me to see that when people engage in issues and vote, then we can win at social change.”

“On our campus we have statues of Tommie Smith and John Carlos,” says Myers-Lipton. “They were two SJSU students who felt compelled to take action because of the racism and poverty in U.S. society, so they decided to take a stand by raising their fists at the 1968 Mexico Olympics. Smith and Carlos left a legacy at SJSU. Today, I ask my students, ‘What is your legacy going to be?’”

Rycenga’s research on abolitionist educator Prudence Crandall (1803–1890) has provided an early example of how education can be a catalyst for social change. The students of Crandall’s academy went on to achieve places of importance in the free black community, affecting movements for change that led up to and past the Civil War. Learn more in a

Rycenga’s research on abolitionist educator Prudence Crandall (1803–1890) has provided an early example of how education can be a catalyst for social change. The students of Crandall’s academy went on to achieve places of importance in the free black community, affecting movements for change that led up to and past the Civil War. Learn more in a