Spartan Women in Sport: Gay MacLellan, ’83 MA Kinesiology

Photo: Courtesy of West Coast Fencing Archive

Photo: Courtesy of West Coast Fencing Archive

Photo: Courtesy of West Coast Fencing Archive

Photo: Courtesy of West Coast Fencing Archive

As a child, Gay MacLellan says she loved to move. She played tetherball and four square at recess at her elementary school in the tiny central California town of Ripon, where she was spotted by a teacher who coached fencing. As a shy 11-year-old girl, she was surprised to find that the strategy and technique of the sport attracted her, with its balletic and sometimes aggressive movements. Within a year, she was competing with the foil—the only fencing weapon that women and girls were allowed to use in competition until 2004, while men were using foil, epee and saber. Decades later, she still remembers the sport’s appeal.

“There’s the beauty of the movement,” says MacLellan, ’83 MA Kinesiology. “You’re a warrior if you fence. The history of fencing is so incredible—it goes way back to when there weren’t guns. Swords were used to settle arguments. I was a shy girl, and it was so unique. It gave me something to talk about with people. As I grew up, I realized how lucky I was to have this avenue to travel the world and get the most incredible education, seeing different cultures. It gave me a career.”

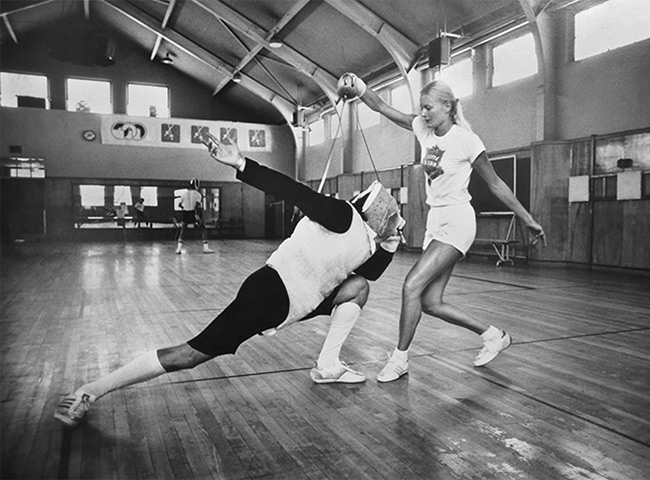

Starting when she was 14, she began training with Michael D’Asaro, a Pan American, U.S. and World Military Saber Champion, and member of the 1960 Olympic fencing team. D’Asaro’s club was located in San Francisco, which meant that MacLellan’s parents had to drive her 90 minutes each way to train every week. Between practice and weekend competitions, MacLellan cultivated a unique fencing style that soon became her trademark.

“I was a skilled technician,” she says. “I learned the movements as perfectly as I could and that’s what served me. Michael trained me to be fast. I perfected that and it took me to the Olympics twice.”

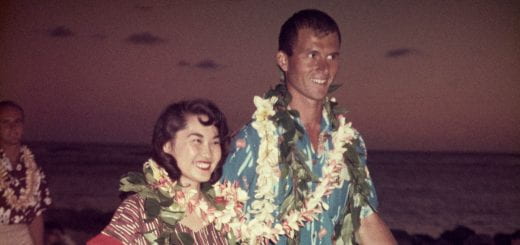

MacLellan fenced for two years at UC Santa Barbara before following her coach to San Jose State in 1974, where he had been hired to coach the women’s and men’s teams. Drawn together by a shared love of sport and drive to compete, the two fell in love and later married.

At SJSU, MacLellan trained with champion fencers Stacey Johnson, ’80 Public Relations, and Vincent “Vinnie” Bradford. The landmark legislation Title IX had passed in 1972, setting a standard of gender equity in sport that the women’s athletics director helped reinforce.

“The women’s athletics department had a very strong athletics director named Joyce Malone,” MacLellan remembers. “She really fought for women and got pretty good equality for us. As our coach, Michael was always a strong supporter of women. We had so much support, the women at San Jose State.”

That support was essential when it came time to compete. MacLellan split her focus between fencing and academics, building her strength, running for speed and endurance, traveling regularly for tournaments. Her hard work brought serious results, including winning the U.S. Women’s Foil Championships in 1974 and 1978—and earning a spot on the Olympic fencing team at 1976 games in Montreal.

“I don’t even remember touching the ground with my feet,” she says. “I was just so amazed at everything. I was pleased with my performance, winning more than I lost. But it was my first major international competition, so I was just overwhelmed. It blew me away.”

MacLellan and her teammate Stacey Johnson qualified for the 1980 Olympics in Moscow, but were unable to compete because the U.S. boycotted the Games. It was a complicated time. As thrilling as it was to make the team, the fact that they couldn’t actually participate affected the fencers. MacLellan retired from competition that same year, switching her focus to teaching fencing, dance aerobics and body mechanics in SJSU’s physical education department. In 1983, she completed her master’s thesis, “A History of the Amateur Fencers League of America,” the governing body that predated the United States Fencing Association.

By studying the history of the sport and the way it had been governed, MacLellan gained perspective on how it might evolve. She stayed active in the sport by refereeing around the U.S., as well as worldwide. Though she and D’Asaro eventually divorced, she remained very active in the fencing community.

“At the time, there weren’t many woman referees, and internationally there were none,” she says. “I was one of the first U.S. women to get an international referee license.”

Unlike competing, which emphasized her individual performance, as a referee MacLellan had to confront stereotypes about women in sport, which she found frustrating. As a national champion, Olympian and unofficial historian of the sport, she grew tired of hearing others question her qualifications.

“International refereeing did get hard,” she says. “Many people did not feel that women were capable of being good referees. I didn’t want to fight that battle internationally. I had already fought that battle in the U.S. I think I was scrutinized a lot more than men were, in what kinds of calls they were making. I had to try to be as perfect as possible to prove that I, as a woman, was capable of being a referee.”

Photo: Courtesy of West Coast Fencing Archive

Despite this, MacLellan was always grateful for the opportunities that the sport afforded her. Not only did she create a career out of competing, teaching and refereeing, she gained confidence, composure and independence that has served her in her life beyond fencing.

“Starting sports as a girl was so helpful in my growth,” she says. “It taught me that I could take care of myself physically. I really felt that if I was going to be attacked, I could handle it. The travel I did as a young girl and teenager, and then in my 20s, was so educational in training me to be independent. I always encourage young girls to get involved in sports early.”

A 2004 inductee into the U.S. Fencing Association’s Hall of Fame and an inductee into SJSU’s Sports Hall of Fame, MacLellan now splits her time between southern Oregon and Vancouver, Washington. It has been years since she has donned her mask, jacket, gloves, knickers, socks and protective gear. She has since found new ways to apply her skills, such as ballroom dancing. Understanding how to approach, assess and react to another person has carried over to every other aspect of her life. She is proud to belong to a tradition of high-achieving woman athletes and has seen the impact that positive role models can have, not only on athletes, but anyone who watches competitive sports.

“To see women perform at high levels, and to hear those women speak and present themselves, I think changes a lot of people’s opinions and outlook on women,” she says. “Sport shows women as confident, strong and capable of accomplishing high goals. In that sense, I really think it does help social change.”