Editor’s Perspective: Gram’s Stories

There’s a photograph of my grandmother that always makes me want to sing the Polish refrain in Bobby Vinton’s “My Melody of Love.” Gram is sitting in her doorway with her black hair covered with a kerchief, spending time with a feathered friend. She’s not singing in the photo, but I would bet she was humming, as she did often.

Not seen in the photo are the pine and spruce trees that surrounded her weathered, gray house in the Adirondack Mountains. Despite all the needles and sticky sap in the yard, she had a flower garden and a crooked, half-uprooted crabapple tree that remained standing through pure tenacity. There was also a barn with a coop that was once full of the family’s chickens.

Gram’s kitchen smelled faintly of aging spices and saltine crackers. I remember sitting with her, drinking lemonade out of a tall, slender glass etched with polka dots. As Gram spoke, she’d rub circles around her aching knees and look into the distance through heavy glasses that would rise and fall on her cheeks as her expression changed. She would slowly tap her foot and rock as she told stories of her time working in the textile mills of New York Mills, New York decades earlier.

She told me about walking to work and having little more to eat than a lard sandwich each day. She would eat half during her first break and save the other half for later. She told me many times about a beautiful girl who worked there, too. But, after Gram died, I learned what she left out: the struggles of the Polish workers, especially the new immigrants—and how they came together to create change.

Inside the mills, fibers floated in the air like snow while workers made fabric on looms. The workers gathered the fibers that collected on the looms and rolled them into earplugs to protect their hearing. Those same fibers stole their voices; inhaling the fibers caused chronic laryngitis. New York Mills was a company town with company housing. There were curfews and rules for appropriate behavior for workers. And not everyone welcomed the Polish mill workers. They were called Polaks and some people spat at them. School children would stand on the rooftops in the winter to shovel snow onto the workers as they walked down the street.

“She was my fondest connection to my Polish heritage and to the sacrifices of her generation and those before hers. Those sacrifices made possible the life I have today, telling the stories of Spartans in San Jose State’s community, stories that inspire respect and hope—and that take me back to Gram.”

The Utica Saturday Globe wrote on July 6, 1907: “For a number of years past Poles have been superseding the employees of other nationalities in the large factories and now they form the bulk of the working population of village. The greater part of these Poles in the mills have come from Russia or Galicia and are among the most illiterate of the lower order of immigrants who seek our shores … At best the Poles in the village are a surly, sullen lot, even when sober; intoxicated, they are savage and dangerous.”

To examine the effects of unlimited immigration, Congress formed the United States Immigration Commission, known as the “Dillingham Commission” (after Vermont Senator William Paul Dillingham) in 1907. According to Harvard University’s Immigration to the United States, 1789–1930 open collection, “The Dillingham Commission had concluded by 1911 that immigration from southern and eastern Europe posed a serious threat to American society and culture and should therefore be greatly reduced. The movement for immigration restriction that the Dillingham Commission helped to stimulate culminated in the National Origins Formula of 1929, which capped national immigration at 150,000 annually and barred Asian immigration altogether.”

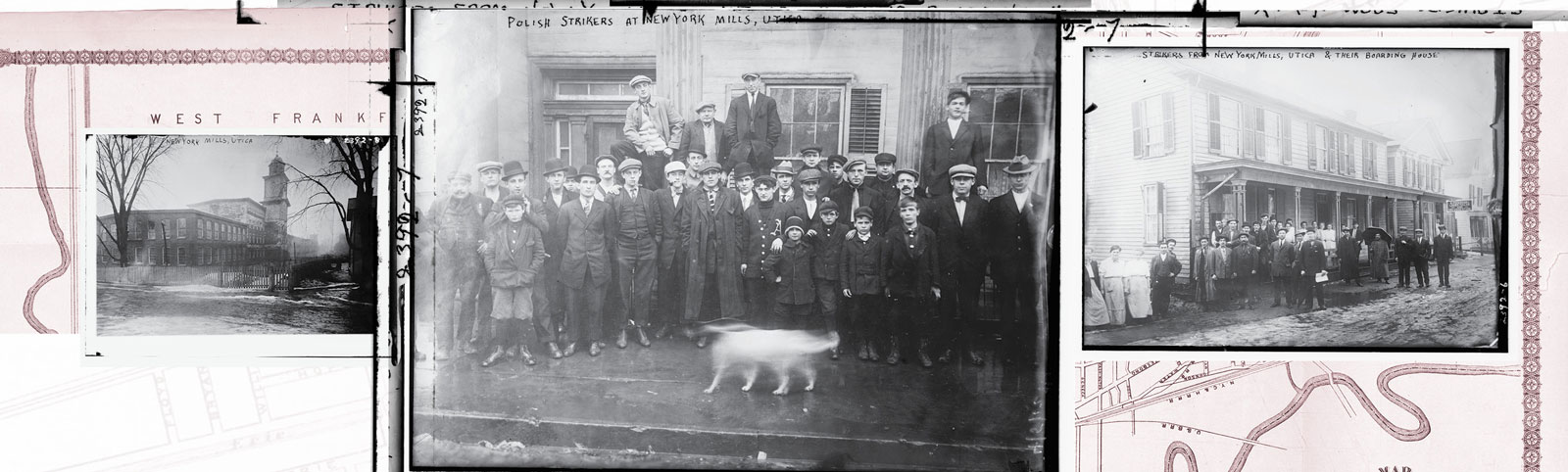

Like many immigrants to the U.S., the Poles in New York Mills were looking for a new, better life. They did what was necessary in that pursuit. The Polish workers went on strike—twice, in 1912 and 1916—for Równosc, Wolnosc, Braterstwo (“Freedom, Equality, Brotherhood”). As a result, their belongings were tossed into the street. The National Guard was brought in to keep order. The company brought in scabs to take their place. The workers held their ground.

All of the mills closed by 1953, but the community remained. To honor the mill workers, a bell was installed in 2000 as a monument to their efforts. Village Trustee John W. Bialek wrote: “We are ‘one’ in showing pride and gratitude to those who carved and paved our paths for us and made us their beneficiaries of a better life in this beautiful village. Many thousands of footsteps have walked the inflexible corridors of those old factories in New York Mills.”

Gram was the only grandparent I knew. The others died before I was born. She was my fondest connection to my Polish heritage and to the sacrifices of her generation and those before hers. Those sacrifices made possible the life I have today, telling the stories of Spartans in San Jose State’s community, stories that inspire respect and hope—and that take me back to Gram.