Peter Caravalho on the Paradox of Japanese-American Internment

This year marked the 75th anniversary of the executive order which sent 120,000 Japanese and Japanese-Americans to internment and incarceration camps across the United States. SJSU’s longtime designer and writer, Peter Caravalho, ’97 Graphic Design, ’16 MFA Creative Writing, curated some historical imagery for the Enduring History: 75 years after Executive Order 9066 story in the spring/summer 2017 issue to recognize this important anniversary.

Photo: Alex Martinez

“I advocated strongly for the inclusion of this subject in our spring/summer Washington Square issue because I believe this story is important, not only for me, but for our community at large.”

In addition to being an accomplished artist and writer, Caravalho has a personal connection to this story. His mother’s family is Japanese-American, and during World War II they were sent to the Gila River Relocation Center in Arizona, an experience that left an indelible impact. Caravalho sought out imagery that he felt illustrated the cultural, economic and political effects of internment on an entire generation.

Caravalho’s mother was sent with her family to an internment camp when she was a young child. “As a little kid, I was aware that my mom was in a camp, but I knew it wasn’t a summer camp,” he says. “When you’re that young … your parents are your everything. Even then, I had an idea that she was a prisoner. How could my mom be a prisoner? What did she do wrong? She was only two years old.”

She later earned two nursing degrees from San Jose State.

In early 2017, after the first executive action attempted to ban Muslims from entering the United States, Caravalho felt that history was threatening to repeat itself.

“Japanese-American internment … would show up in a history book—or if it did, it was three lines,” he says. “That almost made it feel less real. Your parents don’t talk about it, your relatives don’t talk about it, your country doesn’t talk about it. In the ‘80s when [President] Reagan signed the redress, families got up to $20,000 back. I wish—I should still ask my mom about that, how that felt for her. Twenty thousand dollars. How did they factor that?

“I advocated strongly for the inclusion of this subject in our spring/summer Washington Square issue because I believe this story is important, not only for me, but for our community at large.”

Want to learn more? Check out the CSU Japanese American History Digitization Project, a joint archive of the California State University system.

It was important to Caravalho to include the combat service identification badge for the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, an infantry regiment of the U.S. Army composed of soldiers of Japanese descent that served in World War II.

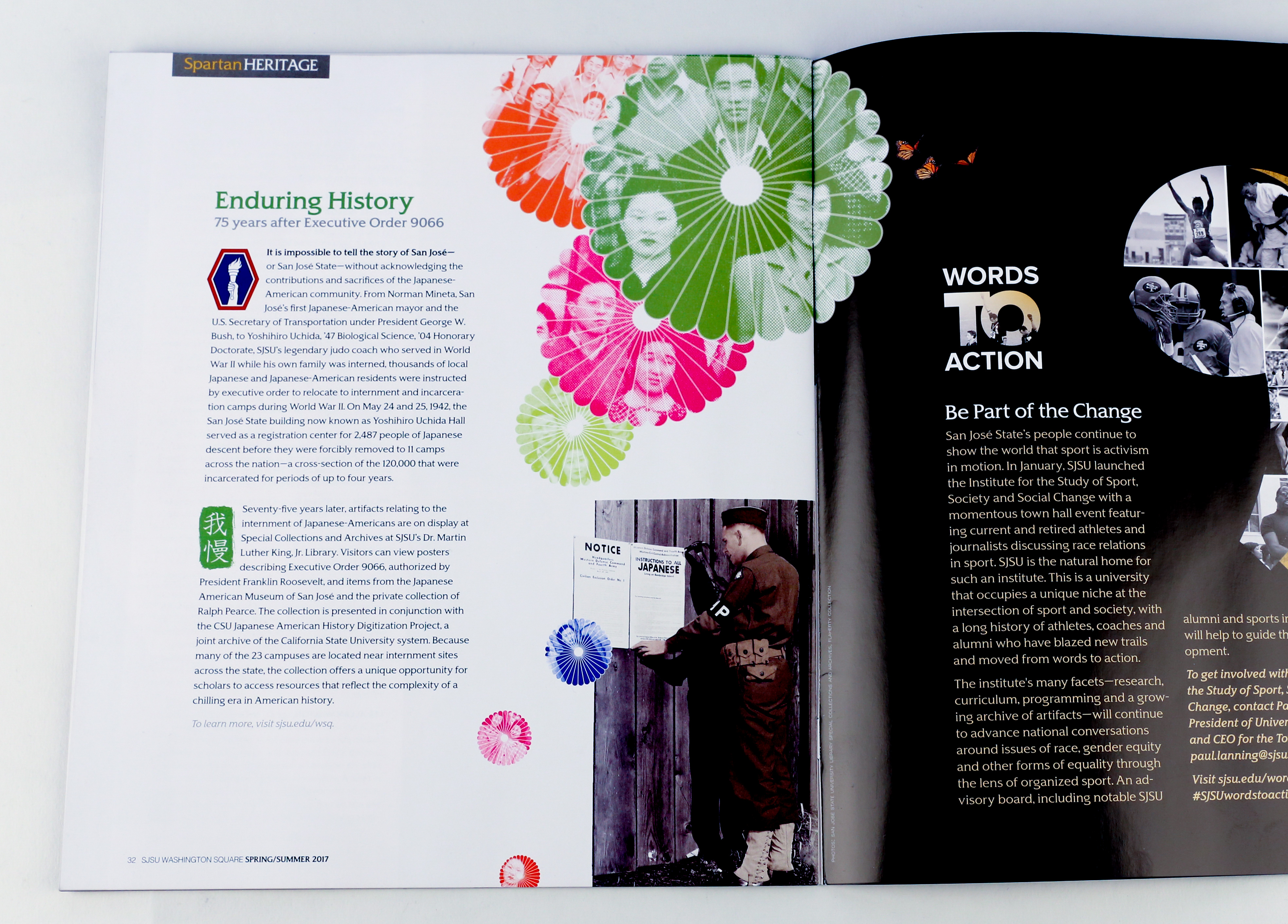

It was important to Caravalho to include the combat service identification badge for the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, an infantry regiment of the U.S. Army composed of soldiers of Japanese descent that served in World War II. “This is from Bainbridge Island in Washington state,” he says. “This is an MP tacking up the poster with the instructions from the executive order: By this date in this location, you need to be here, carrying only so much.”

“This is from Bainbridge Island in Washington state,” he says. “This is an MP tacking up the poster with the instructions from the executive order: By this date in this location, you need to be here, carrying only so much.” Caravalho understands the kanji symbol “Gaman” “to be this idea of endurance and perseverance, particularly in the face of hardships. There was no rioting when [Japanese-Americans] were interned—when they were asked to give up all their possessions and their livelihoods, they just did it. Maybe they felt they needed to prove how American they were … it really does something to a whole generation.”

Caravalho understands the kanji symbol “Gaman” “to be this idea of endurance and perseverance, particularly in the face of hardships. There was no rioting when [Japanese-Americans] were interned—when they were asked to give up all their possessions and their livelihoods, they just did it. Maybe they felt they needed to prove how American they were … it really does something to a whole generation.” Caravalho placed images of the Nisei graduating class from San Jose State inside chrysanthemums, a flower often associated with Japanese national identity. Many of these students had their education interrupted by internment and were not able to complete their degrees. Years later they were recognized at Commencement.

Caravalho placed images of the Nisei graduating class from San Jose State inside chrysanthemums, a flower often associated with Japanese national identity. Many of these students had their education interrupted by internment and were not able to complete their degrees. Years later they were recognized at Commencement.