Educating the Establishment

Activist-scholar Harry Edwards is more convinced than ever that sport is a window to society, revealing a broad range of social and political concerns that affect us all. To see this keenly illustrated, view items from Edwards’ life and work that he recently donated to SJSU, hosted in Special Collections inside the Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Library.

Photo: Christina Olivas

Harry Edwards had to petition to be a sociology major at San Jose State. At the time, he says African-American scholarship athletes had three options when choosing a major: physical education, social work or criminal justice—to prepare for a career as a probation officer. Student-athletes, particularly minority students, were often stereotyped as unprepared for the academic rigor of college. And an athlete’s eligibility could not be jeopardized. Edwards, ’64 Sociology, ’16 Honorary Doctorate, was driven to prove he belonged in the classroom as well as in the gym, where he was the team captain and leading rebounder for the Spartan basketball team and a standout track and field athlete.

For three and a half years, Edwards carried a card around to every one of his professors every Friday to get them to sign off on his academic progress so he would be eligible for intercollegiate athletics. He recalls when the athletic director learned that he was on pace to graduate on time and was in the running for a Woodrow Wilson Fellowship to do graduate work at Cornell University. When asked why he never told anyone that he was carrying a B+/A- average so he could stop getting his grades checked every week throughout the year, he replied: “Because no one ever asked.”

Edwards says his thirst for knowledge, for critical thinking and for continually challenging himself intellectually was born out of his time as an undergraduate student. “The thing I took away above all else from San Jose State was a fierce determination for academic development.” He also still has every book ever assigned to him, “severely underlined and full of notes.”

Edwards was the team captain and leading rebounder for the Spartan basketball team.

Edwards challenged the university and all college athletic programs to diversify their coaching ranks.

Sport for change

His fierce determination drove Edwards away from a potential career as a professional athlete to Cornell, where he challenged faculty members in the graduate program in sociology to accept his dissertation proposal. “Sociology had always studied the effects of dyads, one-on-one relationships, and triads, two-on-one relationships. I looked at organized sports in this country and around the world and was convinced that if thousands or even millions of people would watch and react to a sporting event, there was much to learn from the study of one-to-many.” Edwards eventually convinced the Cornell faculty of the legitimacy of his theory. His two-volume, 1,100-page dissertation, The Sociology of Sport, spawned an entirely new field of study. “Sports are not the toy department of human affairs,” but an area of serious sociological study, as proven through his work over the past half-century.

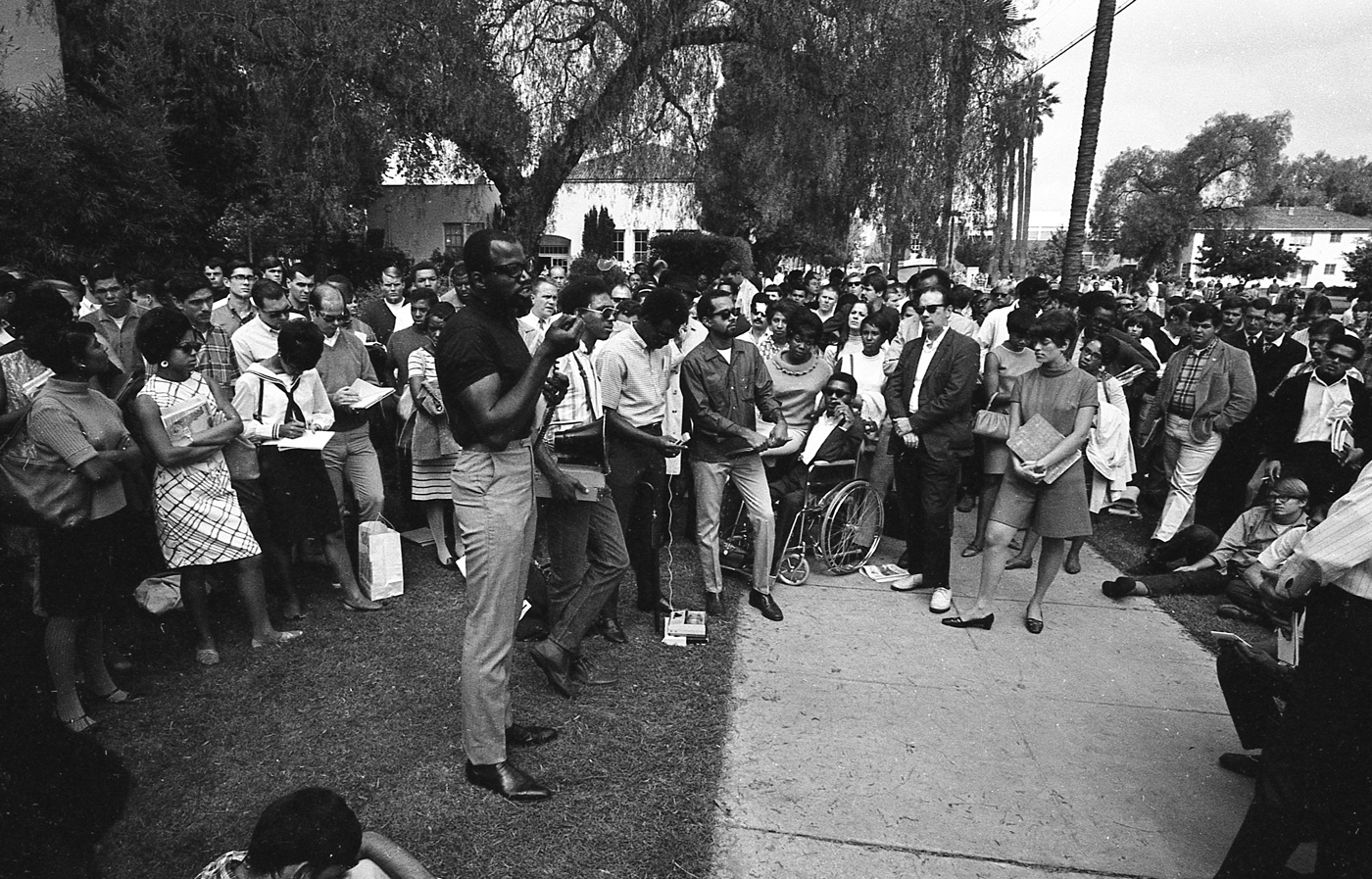

After completing his coursework at Cornell, Edwards came back to San Jose State as a lecturer while writing his dissertation. During this time, Edwards challenged the university and all college athletic programs to diversify their coaching ranks. It was patently wrong, he argued, that African-American student-athletes could compete for colleges at which they could not coach. “Why play where we cannot work?” he reasoned. For that he was labeled a radical.

Out of Edwards’ social activism and SJSU’s famed “Speed City” track program the Olympic Project for Human Rights was created. Edwards served as a lightning rod for a movement that called upon the United States Olympic Committee (USOC) to diversify its ranks. “Why should young black men run for an organization that will not allow them to join?” Edwards recalls.

Edwards shifted his focus to the Olympics because, he says, what was going on at San Jose State was happening nationally. A “wave of rebellion” washed over college campuses in places like Syracuse, Berkeley, University of Washington, Wyoming and St. Mary’s College in Moraga. Basketball players were demanding “an education that reflected the realities of their lives, not just mainstream, white America,” says Edwards. “There were 105 institutions that looked at San Jose State and said ‘If they can change it, we can change it.’”

On a television in Canada, Edwards watched the iconic moment in 1968, a silent statement by Olympic medalists and SJSU student-athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos on the victory stand. Edwards appeared on a televised interview to prove he was not in Mexico City or even in the United States during the Games. He recalls of that time, “If I had been in Mexico City, I would have been seen as being responsible for their safety. If I were not there, the USOC would be responsible for caring for and protecting these young men. They could not abdicate that responsibility.”

The aftermath of the 1968 Games was both personal and global. Edwards endured death threats and an ongoing FBI investigation commissioned by J. Edgar Hoover himself. Ultimately, he was terminated from his teaching position at San Jose State. But, in an act of solidarity with the movement, Nelson Mandela posted an Olympic Project for Human Rights poster in his prison cell. Edwards says, “It was the first time Mandela realized that sports could be used for social change.”

Photo: Christina Olivas

Field of influence

“Everything I am, ever was and ever will be started at San Jose State.”

“Most people want to believe that their lives have been meaningful, that something, someone, or some situation by some humane measure is somehow better,” wrote Edwards in the prologue to The Struggle that Must Be: An Autobiography. At age 35, when the book was written, Edwards had already set a lifetime of change in motion—from his earliest memories of growing up in East St. Louis to pivotal experiences as a San Jose State student-athlete to working for change with his future wife and then-SJSU student Sandra Boze, one of the members of the Olympic Project for Human Rights, to his controversial faculty appointment at UC Berkeley that was publicly condemned by Governor Ronald Reagan (despite Edwards’ Ivy League credentials). Inspired by the likes of James Baldwin, Ralph Ellison, Lorraine Hansberry and Maya Angelou, who wrote the introduction to Edwards’ autobiography, as well as blues and jazz artists, Edwards says, “their words were so touching. I wasn’t reading them. I was living them.”Edwards is now UC Berkeley professor emeritus of sociology, having spent more than 30 years “inciting students to think” through his lectures and activism. In time, too, the very establishment that Edwards challenged in the 1960s came to call upon him for counsel. Edwards marvels at the fact that three of the greatest influences on social issues in sport in the past half-century all came from San Jose State, pointing to fellow alumni Peter Ueberroth and Bill Walsh. “There’s something in the water at San Jose State,” Edwards says, smiling.

When Ueberroth was Major League Baseball commissioner, he brought in Edwards to advise MLB on social issues in the aftermath of former baseball player and MLB executive Al Campanis’ racist remarks on “Nightline” in 1987. Edwards had previously worked with Walsh and the San Francisco 49ers to develop training and retention programs that have since been adopted throughout the National Football League, and Edwards has advised numerous other sports organizations on race relations and social issues throughout his career. He continues to work with the 49ers to this day.

A sought-after speaker and lecturer, Edwards has been feted with numerous awards and honorary degrees over the years, but his return to San Jose State to receive an honorary doctorate in 2016 was special to him. “This one means the world to me,” he says.

“Everything I am, ever was and ever will be started at San Jose State,” Edwards adds. “I’m saying the same things today I was saying back then. I haven’t changed a bit. The establishment has.”

![]() Watch Edwards’ commencement address and view a photo gallery from his campus visits this spring.

Watch Edwards’ commencement address and view a photo gallery from his campus visits this spring.