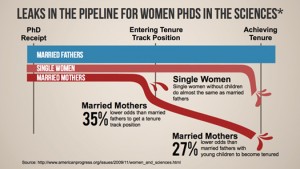

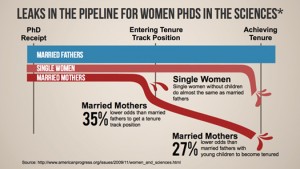

The percentage of PhDs in Biology awarded to women has increased from only 15% in 1969 to 52% in 2009. Even with these dramatic gains in the number of female PhDs, women currently make up only 36% of assistant professors and 18% of full professors (1). This drop-off in female representation after graduate school is often termed the ‘leaky pipeline’ and has far-reaching consequences for the state of science and our economy.

Figure from Tools for Change

A recent article in PNAS details one hole in the academic pipeline for women: elite labs run by male, but not female, professors are less likely to train female graduate students and postdocs. Labs were qualified as elite if the PI was awarded Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) support, a member of the National Academy of Science (NAS), or had won a major award like the Nobel Prize. Labs headed by men had fewer female graduate students (47%) and postdocs (36%) than labs headed by women (53% and 46% respectively), but in elite labs run by male professors, female trainees were even more poorly represented. In contrast, the gender makeup in labs headed by women was unchanged with elite status. The authors found that men were 25% more likely to complete their postdoctoral work in the lab of a NAS member and 90% more likely to postdoc in the lab of a Nobel Laureate. Women win graduate and postdoctoral fellowships at rates proportional to their representation in the applicant pool, suggesting that female trainees are as qualified male trainees. The reason why this deficit matters is that assistant professors in research universities are likely to come from elite laboratories (see full article here).

Why elite labs train fewer women was not determined in this study, but most studies on the leaky pipeline tend to focus on two areas: implicit bias and the lack of family friendly policies. While the days of women being explicitly barred from pursuing certain careers are over, implicit bias against women is still alive and well. When given identical resumes, both male and female PIs were more likely to rate male candidates favorably, choose higher starting salaries for male candidates and offer male candidates more career mentoring (2). In European countries where tenure committees are randomly assigned, female candidates are less likely to receive tenure if their review committee is all male but receive tenure at similar rates as men if they have a mixed review committee (1). In a recent survey, 16% of female scientists report instances of sexual harassment in the workplace and this harassment can have far-reaching consequences as vividly illustrated with the #ripples of doubt twitter conversation. It is well known that certain labs are more family friendly than others and female postdocs are more likely to take that into consideration when choosing a lab. Women who have children during their postdocs are much more likely to decide against a research career than male postdocs with children, whereas female postdocs with no plans of having children are as likely to choose a research career as male postdocs with or without children (3).

What Can We Do To Plug the Leaks?

Recruiting and maintaining a diverse scientific workforce is something we all will benefit from (and much of what I’ve discussed here also applies to other groups traditionally underrepresented in science). This is an area of science policy that needs to be tackled at all levels. Locally, we can try to acknowledge and overcome our biases in our laboratory and department hiring and mentoring. If you are on a conference organizing committee, help to recruit female speakers and work to provide child care arrangements, especially paid options for graduate students. Institutionally we can work to implement family friendly policies, like those instituted by UC Berkeley’s Faculty Family Friendly Edge Program (you can even use this cost simulator to see the true cost of not implementing these policies at your institution). At the federal funding level, we can advocate for the expansion of programs like the NSF’s Career-Life Balance supplement that provides funds for a technician while the PI is on maternity leave.

In this short post I’ve only scratched the surface of these issues. Below are some suggested sites if you want to learn more:

Tools for Change in STEM

Nature Special Edition on Women in STEM

STEM Women

The UC Faculty Friendly Edge

UC Davis ADVANCE

Old Boys’ Lab–nice write-up about the PNAS study by AAAS Mass Media Fellow Jane Hu