Coastsider becomes an honored elder, Professor writes book recapturing a lost history

Originally posted by the Half Mon Bay Review Oct. 26, 2011

By Stacy Trevenon

Two years ago, a woman who Coastside professor Jeff Fadiman says he never met called from Atlanta to ask if he was “the “famous Jeff Fadiman.”

Fadiman politely responded that she had the name right, but he wasn’t famous.

The woman disagreed.

“She said, ‘You are famous,'” said Fadiman. “‘I’ve just come from the Meru and you are famous because of your book.”

Her mention of Fadiman’s writings about Meru history took the El Granada resident back more than 40 years. He is a 21-year San Jose State University professor of global marketing with emphasis on high-risk regions such as Africa. But back then, his efforts to preserve the oral tradition and history of a people whose history had been all but wiped out brought him gratitude, reverence and the title of “elder” from those people.

In 1969, Fadiman had lived on the slopes of Mount Kenya and had become interested in the Meru.

Their region had been conquered by the British in the early 20th century. The conquerors had indoctrinated their culture in place of that of the Meru. Their children, said Fadiman, had been forced into schools to learn British history, not their own. “Meru history and culture were denigrated as primitive and savage,” he said. “Every single thing had been lost.”

So Fadiman traveled to huts deep in the bush to seek out the oldest living members of the Meru and ask them to teach him the wisdom of their elders as they had been taught.

The oral traditions in the elders’ memories go back many generations, Fadiman said. “Each elder I talked to directed me to someone still older who had taught him,” he said.

Fadiman interviewed more than 100 elders in hundreds of meetings, and then set about organizing his information.

“My job was to take all the tales I had been told, sift them for the truth, and then weave them into a coherent narrative so that the Meru yet unborn could read and learn what it meant to be Meru,” he said.

What it “meant to be Meru,” he said, was to live as a warrior when young, connect with the “nkoma” or ancestral spirits as one aged and then pass through the tunnel that led from life to death.

Little moments showed him he was on the right track.

He said that an old man – one of many – told him that “God kept me alive so I can give you this information. Please write it so my grandchildren will know what it is to be Meru.”

Fadiman took his material back to the United States, wrote a dissertation, received his doctoral degree, became a history professor and moved on with life. In time he received Fulbright scholarships, and spoke more than once before the Commonwealth Club of California. He married and started a family.

But unseen factors were at work to bring that book and Fadiman back to Meru.

Kenya government official Kiraitu Murungi was in Washington D.C. and spotted Fadiman’s book in a bookstore. Then Meru journalist Titus Murithi, who writes for an English publication in Meru, seeking sources for his articles, contacted Fadiman – by coincidence, he said, on the same week the Atlanta woman had phoned.

The Minister of Education invited Fadiman to Meru to meet with the people whose history he had helped preserve.

So in August, Fadiman flew to the Kenya airport, then took a tiny bush plane to within an hour of Meru. It landed at the still-active safari camp of “Born Free” author George Adamson, and Fadiman made the last leg by car. The trip was arduous, but proved unforgettable.

On Aug. 21, Fadiman spoke to Meru leaders in labor, church, education and professions, at the Safari Hotel, the largest venue organizers could find. He spoke to a crowd of 400 in the morning and to 500 that afternoon.

He recounted the story of what happened four decades ago. Then, he said, he held up two of his books and “said in a voice of thunder, ‘You are their grandchildren. Here are the books. Have I not kept my word to your ancestors?'”

Their response was his answer. “I got a standing applause and ululation,” the resonant, particularly African sound, something like a cross between a cry and a whoop.

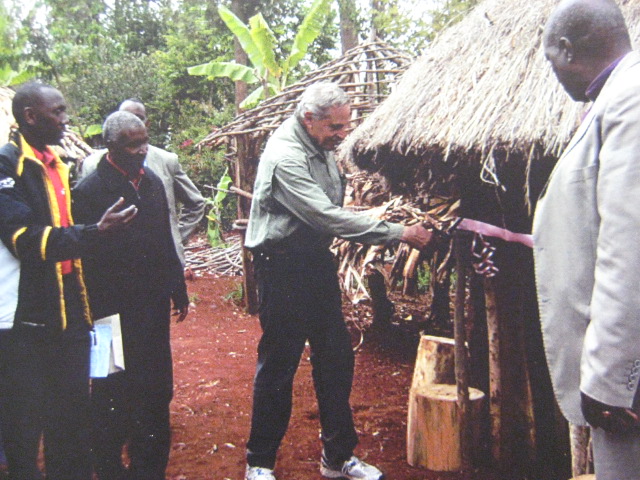

And that was not all. In a subsequent ceremony the minister of education proclaimed Fadiman the “father of Meru history” and made him a Meru elder by bestowing on him the “cloak of authority” and the “staff of authority.” Upon leaving Meru, Fadiman was “swarmed by laughing, dancing Meru men, women and children from the moment I got out of the car to the moment I left Meru.”

“I consider this the greatest honor of my life,” he said.

The celebrations included an impromptu, spontaneous few moments of delighted dancing, singing and laughter, with the minister of education. That resulted in an email from Fadiman’s driver, who had seen the impromptu cavorting on national television.

“I am so proud to be your driver,” the message ran, “because you could never have danced a step unless I drove you there.”

Limited copies of Fadiman’s book are available through Amazon.