Welcome to Fall 2020. Hopefully we are settling in nicely to the new semester. My name is Allyson Gomez, SJSU alum and adjunct lecturer. What a year! I was a mentor for the Online Summer Certificate Program designed by eCampus, the Center for Faculty Development, and the Office of Diversity. This program helped prepare over 900 faculty members for online teaching. You can check out more offerings on the eCampus Support Page. I had a full circle moment this summer, being able to mentor and work with faculty who taught me 10+ years ago.

During the course, one question kept coming up: how do we get to know our students virtually, how do we keep them engaged virtually, and how do we foster a community or classroom environment virtually? Online learning is not new. The University of Phoenix offered their first online program in 1989, and through the years online degrees have become more widely accepted. Online technology has advanced by leaps and bounds with more efficient internet connectivity and improved video conferencing capabilities. More recently, people’s opinions have changed about remote learning due to COVID and shelter in place orders. Just as managers resisted employees working from home or remotely – some faculty resisted virtual learning and online courses over concerns that students may not be truly engaged and immersed in learning the subject matter. However, given the current pandemic we must challenge our preconceived notions on virtual learning for education and safety sake.

Regardless of format, I believe that the fundamental concepts of teaching and learning are the same and have not changed. It requires a shift in mindset (perhaps slight, small, or a big change depending on the technology learning curve) in order to succeed. We must teach and foster relationship building with our students through lesson planning, class interactions, activities, assessments, homework, and office hours.

So how do we foster a dynamic, inclusive learning environment for our students in a virtual world?

Here are 8 simple engagement strategies, because 8 is great!

This blog focuses on Zoom’s feature as it is SJSU’s webinar of choice…

#1: Camera On: There’s a big debate about mandating camera preferences because of accessibility, bandwidth, and private learning spaces. I understand the concerns, and ultimately believe that turning on the camera allows for increased media richness when we cannot meet face to face. So much gets lost in translation in the virtual world. A camera can help build connections and assist in reading moods and reactions. It also encourages accountability (my students cited they would be more likely to multi-task and zone out if cameras were off during class). Let’s encourage more formal, respectful, and engaging interactions by keeping the camera on. At the very least, I ask for cameras on during ice-breakers and in breakout rooms. Note: I make a disclaimer that it is okay if there are kids or roommates coming in and out of the background; it’s part of 2020. If a student is unable to have his/her camera on, let the class know via chat. No explanation needed. ![]()

#2: Ice–Breakers: I am a huge fan. These are low-stake opportunities for students to learn how to speak in front of a camera and bond with others. What is your major/year? What city do you live in? Favorite sports team? Binge worthy show? As a business lecturer, I may base questions on our readings or future activities: one word value, name a company that does branding well (no repeats), who is a thought leader, etc. Think of fun check-in ideas. ![]()

#3 Breakout Rooms: Another thing we miss out on in the virtual space is having impromptu conversations. Practice organizing folks into groups before class, during breaks, during activities, or at the last 5 minutes of class. This can be great during long classes and gives students a chance to bond with one another. Zoom is now rolling out a feature (5.3.0) where students can self-select into rooms—making it more convenient for everyone involved. [Pro tip: Most students may groan at group work, but they cheer for breakout group activities during class].

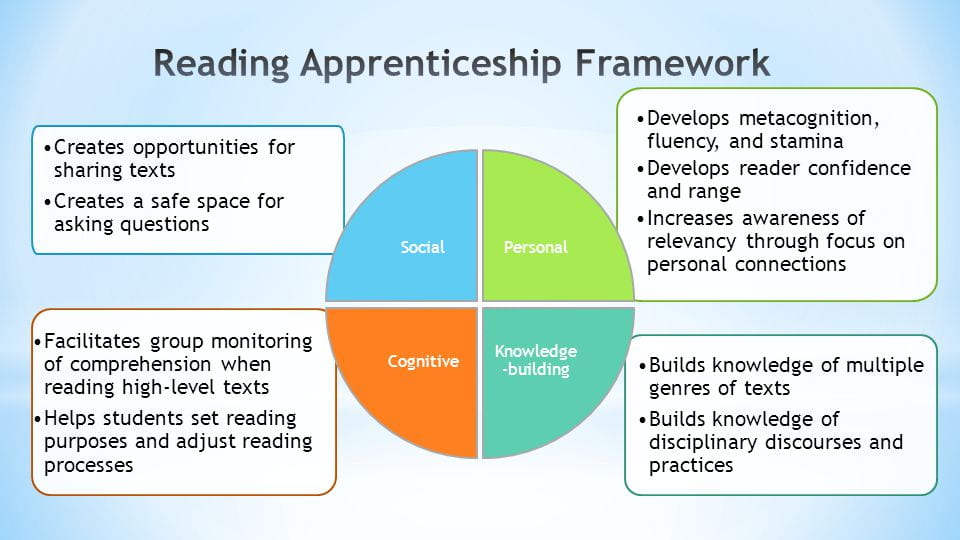

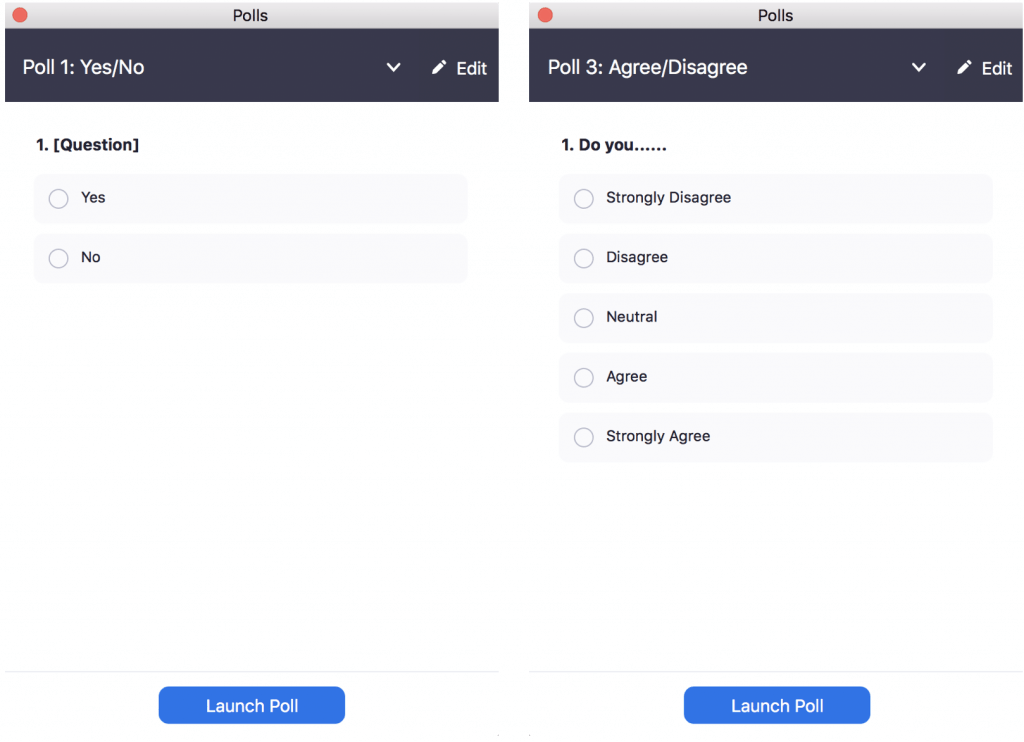

#4 Polling and #5 Chat: Engagement is key. Changing it up is key. What better way than to use Zoom tools? I use these tools throughout my lectures and concept explanations. In the physical classroom, I would normally have students walk over to the right or left side of the room as I ask binary True/False questions or choose option A or B stance on ethical dilemmas. I cannot quite tally 50 folks walking around their respective rooms, so I have introduced quick polling by creating a blank question with a “yes” or “no” answer choice. This allows me to receive rapid feedback from the class. I will ask the class: Are we ready for a break? And launch the blank poll question: Yes/No. Did the manager act in the most ethical way? Yes/No. I read back the feedback, 75% said no, tell me more. This works for True/False and 5-point rating scale questions too. When a poll cannot quite capture the essence, or I want more qualitative or subjective answers, I use the chat feature– 75% said no and 25% yes. Tell me more in the chat. While we wait for folks to type, can two people unmute your microphone and answer why you selected “Yes” or “No?” I spend time reading the comments out loud and ask for additional insights. [Pro tip: If a student can do the dishes or workout during a live class – maybe the lesson can be a recording].

As people share their insights or present topics in class, the #6 Reactions feature helps students express emotions or applaud classmates. These 5 second pop up emojis build classroom interactions without being too distracting. I encourage students to use the reactions tool.

Another way to solicit reactions and engagement is through screen sharing and allowing #7 Annotations. While sharing your screen or PPT, students can add their own drawings or notes. You can also put up a white board and have students draw for a while whether they are literally connecting the dots between two concepts, playing Jeopardy, or doodling. Using breakout activities and different modes of interaction can increase engagement. Note the tools may look different based on your device and OS (Windows, Mac, or Linux).…which leads me to…

#8 Breaks. Ironically taking time away from the class can really boost the brain and further student engagement. Think of it as a mini recharge or caffeine hit. Though a nice cup of coffee or energy drink works too. [Pro tip: Take 30 seconds and look away from your screen right now! Your eyes will thank you]. ![]()

After speaking with colleagues, the biggest concern this semester (aside from learning new technologies) was getting to know your students, keeping them engaged and fostering a community, virtually. Hopefully, I’ve shared some useful ideas to help you better engage with your students.

In future posts, I’ll dive deeper into engagement and fostering an online community through assignments, before/after class, office hours, feedback, and more. 2020 has thrown a lot of new challenges at us. And through all of this, I am proud to be part of the SJSU community. We have been resilient and come together. If you have any questions or want to brainstorm student and classroom engagement ideas, send me an email at allyson.gomez@sjsu.edu. Thank you. Stay safe (and sane).