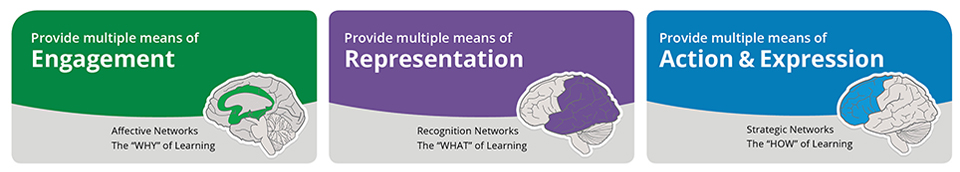

This month, we’ll take a look at the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principle of engagement – the “why” of learning for students. The CAST UDL Guidelines on Engagement provide more detailed information on multiple ways to motivate and tap into the interests of learners.

Image Source: CAST UDL Guidelines, http://udlguidelines.cast.org

Online Discussions as a Means to Engage Learners

“There is not one means of engagement that will be optimal for all learners in all contexts” (CAST, 2018) so in this post, I will explore one means that I have used – online discussions. Online discussions are an integral component of online courses and can be used as an alternative means of expression for an in-person course to promote student engagement, facilitate the exchange of ideas, and deepen understanding of course content. For online courses, these discussions provide necessary social presence and interaction (instructor-student, student-student, and student-content) as similarly achieved in a traditional classroom and support student learning perception and a sense of community.

Purposeful design that incorporates online communication between students and instructors, as well as between students and peers fosters effective learning interaction (Johnson, 2017)

Online discussions require more than just an interesting question or prompt although this is a crucial component. Here are a few key features and resources to address in designing and facilitating asynchronous online discussions.

Promote Netiquette and Provide Feedback Due to the absence of visual and auditory cues in online discussion forums, a netiquette policy sets upfront expectations for constructive online communication and behavior. Providing netiquette rules and guidelines lays the foundation for a safe, shared learning environment.

Active participation by the instructor reinforces the model behavior as established in the netiquette guidelines. Additionally, instructor involvement and feedback encourage student participation. Further, providing detailed feedback and comments to student posts early in the semester helps develop good habits and discussions that meet expectations. (Simon, 2018)

Set Clear Expectations A clear expectation of depth of discussion post, frequency, interaction with peers and instructor, and evaluation criteria facilitate better student engagement (Johnson, 2017). This helps students’ awareness of what is required and facilitates not only participation but engagement with peers and the content. There are various protocols for structuring online discussions but in general, all share a well-defined objective, set clear interaction roles and rules, and clarify deadlines. The Save the Last Word for Me protocol has been shown to support student engagement and ownership of discussion. (deNoyelles, 2015)

Add Relevance “Why do I need to know this?” is a common question amongst learners. The instructor can offer opportunities for students to see the relevance and value of course content by providing a question or prompt and connecting it to a current event or real-world model.

Add multimedia Beyond text, student to content interaction can be boosted with the use of multimedia – image, audio, video, and animation. Visual tools engage students by creating a connection between student and content and reinforce discussions. (Harris, 2011) Further, “context-based videos in online courses have the potential to enhance learners’ retention and motivation.” (Choi, 2005)

Provide a Rubric for Assessment Online discussions can be assessed from a surface (participation) and/or deep level understanding (critical thinking and application of course content), depending on the learning objective and design for that particular discussion assignment. (Johnson, 2017) Although online discussion assignments can either be graded or non-graded, graded posts incentivize both student participation and quality of posting. For graded discussion posts, the use of a rubric is beneficial as it defines assignment expectations (e.g., clarity, critical thinking, grammar, and word count) for both the student and instructor. Henri’s five key dimensions of content analyses can be used to evaluate the content and engagement level of student discussion posts and serve as the basis for the instructor’s own grading rubric.

Summary of Henri’s Five Dimensions of Content Analyses and Indicators for Engagement

| Description of indicators | Dimension |

| Student has participated in posting to the discussions area to the group. | Participative |

| Student text focuses on interacting with other group members in a supportive way yet does not address the content topic. | Social |

| Student responds to other group members by discussing specific items addressed by other members. | Interactive |

| Student begins to ask additional questions regarding the topic content to other group members and begins to make inferences. This writing demonstrates development of his/her learning process on the topic. | Cognitive |

| Student writing demonstrates that the student is reflecting on their content knowledge through a critical lens of self-questioning and self-regulation. | Metacognitive |

Table: Summary of Henri’s (1992) Five Dimensions of Content Analyses (Henri as cited in Johnson, 2017)

To learn more about the pedagogy of discussions, check out the eCampus Guide (Canvas log-in required).

Tech Tools to Facilitate Online Discussions

There are various tools that can be used to facilitate online discussions. Canvas Discussions and Piazza are both supported by eCampus.

Canvas Discussions is probably the easiest tool to set up and use as it is a feature of the Canvas LMS. Canvas discussions can be graded or not and have the option to include a customized rubric.

And, check out the upcoming February 17th eCampus workshop Canvas IV: Creating Community with Discussions, Groups, Chat, Collaborations, & Conferences (Online) to learn more about implementing Canvas Discussions.

Piazza is a wiki style platform that integrates with the Canvas LMS and encourages collaborative student engagement. Take a look at some Piazza Professor Success Stories.